Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a condition where kidney dysfunction occurs in the setting of liver disease, typically in cirrhosis. The classification and therapies for HRS have evolved.

Pathophysiology:

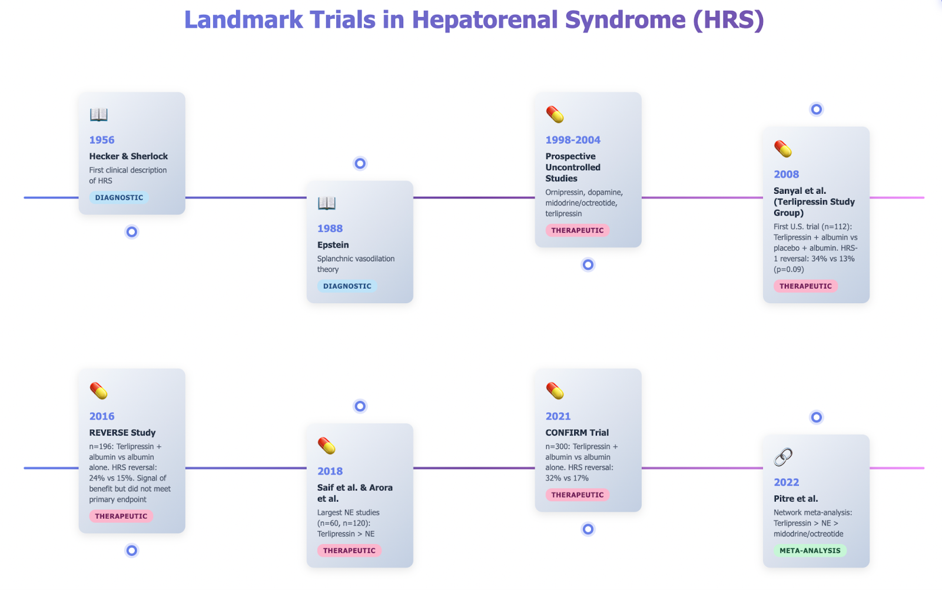

In 1956, Hecker and Sherlock detailed the clinical presentation of HRS. This was further elucidated by Epstein et al. in 1988 with the splanchnic arterial vasodilation theory. The splanchnic circulation consists of the gastric, small intestine, colonic, pancreatic, hepatic, and splenic circulations, arranged in parallel and containing ~20-25% of the circulating blood volume. It drains into the liver via the portal vein, which then drains into the IVC via the hepatic veins. HRS results for increased splanchnic capacitance due to venous and arterial steal from the systemic circulation.

Martell et al. discussed the pathophysiology of HRS, including hemodynamic and physiologic mechanisms.

- Increased vascular resistance within a scarred, cirrhotic liver causes a backup of blood into the portal system, resulting in portal hypertension.

- Elevated pressures increase shearing of the splanchnic vascular endothelium, leading to local upregulation/overactivity of nitric oxide (NO) production.

- Other vasodilators, such as prostacyclin, carbon monoxide, endocannabinoids, and Angiotensin (Ang1-7), are also increased due to systemic inflammation.

- Systemically, there is increased norepinephrine (NE) and angiotensin II (Ang II) activity to maintain peripheral perfusion, but this can result in vascular desensitization over time.

- Receptors for vasoconstrictors, such as endothelin-1, can be desensitized by receptor desensitizing proteins. The RhoA/Rho kinase pathway controlling smooth muscle constriction can also become impaired.

- Concurrently, elevated splanchnic pressures will damage the intestinal lining, allowing bacterial translocation into the portal circulation, where endotoxin release increases cytokines such as TNF-alpha, leading to vasodilator upregulation.

- Additionally, to accommodate the increased vascular pressure, VEGF stimulates pathological angiogenesis to increase splanchnic capacity.

- The effective low central blood volume state due to splanchnic steal causes sympathetic overactivation, resulting in renal vasoconstriction and reduced GFR.

- This upregulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) and arginine–vasopressin (ADP) pathways, leading to further sodium and water retention.

When this delicate balance is disrupted by infection (such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), gastrointestinal bleeding, or large-volume paracentesis without albumin, HRS can be triggered. In advanced cirrhosis, high output diastolic cardiomyopathy (eventually systolic) and low SVR can worsen kidney hypoperfusion. Additional factors, such as cholestasis and adrenal dysfunction, may contribute to tubular damage and worsen renal outcomes.

HRS Classification and Diagnosis:

The International Club of Ascites (ICA) established and updated the consensus diagnostic criteria for HRS, which were most recently updated in 2019. This was further elaborated in the 2021 Practice Guidance of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). HRS-Acute Kidney Injury (HRS-AKI) is characterized as a pre-renal type of acute kidney injury that does not respond to volume expansion. Although HRS is defined by the absence of structural kidney damage, prolonged or severe episodes may lead to HRS-Chronic Kidney Disease (HRS-CKD).

HRS is best understood as a temporal condition—more acute than chronic—rather than adhering to the older binary classifications of type 1 and type 2. Clinical experience indicates that patients typically do not fit neatly into these categories; instead, HRS often presents along a spectrum that reflects the underlying physiology of cirrhosis. This evolving understanding has introduced new terminology, such as HRS non-AKI, which refers to the persistence of HRS physiology after the acute phase resolves.

Patients are now classified into three categories based on the timing and duration of kidney dysfunction:

- HRS-AKI: Previously known as type 1 HRS, this refers to acute kidney injury in patients with advanced cirrhosis and ascites. It may coexist with tubular injury, proteinuria, or pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- HRS-AKD: This applies when kidney dysfunction lasts less than 90 days.

- HRS-CKD: Previously known as type 2 HRS, this classification is used when kidney dysfunction persists beyond 90 days. Patients with pre-existing CKD (e.g., diabetic nephropathy) who develop HRS-AKI are classified as having HRS-AKI on CKD.

In general, HRS is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Parenchymal disease must be ruled out. A diagnosis requires bland urine, the absence of shock or nephrotoxic medications, the presence of cirrhosis with ascites, and a lack of kidney improvement following volume expansion or diuretic withdrawal after at least 48 hours.

A common challenge is distinguishing between HRS-AKI and acute tubular necrosis (ATN). A meta-analysis by Puthumana et al. found that levels of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) and urine interleukin-18 (uIL-18) can help differentiate between patients with ATN and those with other forms of kidney impairment in individuals with cirrhosis.

| Diagnostic Parameter | HRS-AKI | ATN |

| Urine Sediment | Bland, hyaline casts | Muddy brown granular casts, renal tubular epithelial cells |

| NGAL (Neutrophil Gelatinase–Associated Lipocalin) | ~110 μg/g creatinine | 220–244 μg/g creatinine |

| FeNa* (Fractional Excretion of Sodium) | < 0.2% | > 2% |

| FeUrea (Fractional Excretion of Urea) | < 30% | > 30% |

| Urine Sodium | < 10 mEq/L | > 10 mEq/L |

*Limited in cirrhosis as baseline sodium retention and diuretic use may confound interpretation, but highly sensitive when < 0.2%

Treatment:

The treatment history of HRS has primarily focused on correcting underlying hemodynamic disturbances. Various strategies, such as albumin filtration and portosystemic shunting, have been explored but have yielded limited and inconsistent benefits. Among these, vasoconstrictor therapy targeting splanchnic vasodilation has emerged as the most effective approach, typically focusing on V1 adrenergic receptors.

Current vasoconstrictor therapies for HRS include midodrine (an alpha-1 agonist), octreotide (a somatostatin analogue that reduces NO synthesis and splanchnic vasodilators such as glucagon and vasoactive intestinal peptide), terlipressin (a V1 agonist), and NE (also an alpha-1 agonist). Although much of the original data comes from small-scale studies, more robust evidence has accumulated over the past two decades. Albumin is often co-administered with these agents to enhance efficacy by improving arterial blood volume. While no study has definitively shown albumin to be superior to crystalloids, its use is intuitive in cases of cirrhosis, given the common occurrence of hypoalbuminemia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and its potential pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects.

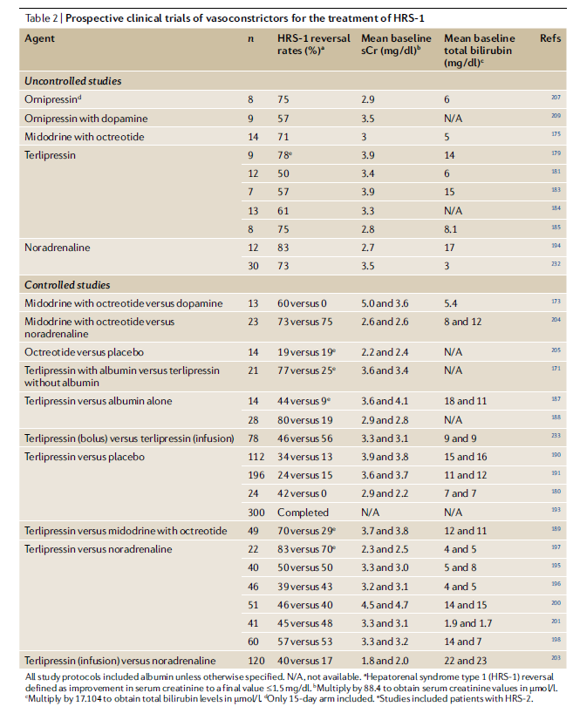

A comprehensive review highlights significant clinical trials (see table at end). Early controlled studies in the late 1990s suggested that combining midodrine with octreotide was more effective than dopamine and comparable to NE. From 1998 to 2004, prospective uncontrolled studies investigated a variety of vasopressors, including ornipressin, dopamine, midodrine with octreotide, and terlipressin. Subsequently, controlled trials of NE began in 2007.

In regions outside the U.S., terlipressin has been reported to have reversal rates of approximately 40-80%. Despite its long-standing approval in Europe, Latin America, and Asia, the adoption of terlipressin in the U.S. was initially delayed by early trials that did not meet primary endpoints. The 2008 Sanyal study showed promising HRS reversal rates of 34% versus 13% with a placebo but narrowly missed statistical significance (p=0.09). The 2016 REVERSE study found a similar trend (24% vs. 15%) but also did not meet its primary endpoint. Finally, the pivotal 2021 CONFIRM study demonstrated efficacy, reporting HRS reversal rates of 32% versus 17% (terlipressin plus albumin versus albumin alone), which led to FDA approval in 2022. The study noted higher respiratory complications, including more respiratory-related deaths (11% vs 2%), and no improvement in 90-day mortality (51% vs 45%). Notably, treated patients underwent fewer transplants (23% vs 29%) despite similar MELD scores, a key concern given the disease ultimately requires transplantation.

It is important to recognize that no large, multicenter randomized controlled trials have directly compared norepinephrine with terlipressin. Most of the available evidence comes from small studies (typically fewer than 100 patients), such as those summarized in the Velez review, along with other investigations limited by weaker methodology or design issues. A 2014 systematic review of four early trials reported similar reversal rates between terlipressin and norepinephrine. Similarly, a 2017 Cochrane review comparing terlipressin with other vasoconstrictors found no significant differences between terlipressin and norepinephrine.

More recent analyses, however, have produced different insights. For example, a 2022 systematic review by Pitre et al. reported that, when compared with placebo, terlipressin demonstrated higher rates of HRS reversal than norepinephrine (142 vs. 112.7 reversals per 1,000), and that norepinephrine outperformed midodrine plus octreotide (67.8 reversals per 1,000).

In summary, current evidence generally supports terlipressin and it is the preferred therapy in many academic society guidelines. Still, definitive confirmation is lacking due to the absence of large head-to-head trials, and considerations such as cost-effectiveness and terlipressin’s side-effect profile remain important unresolved factors.

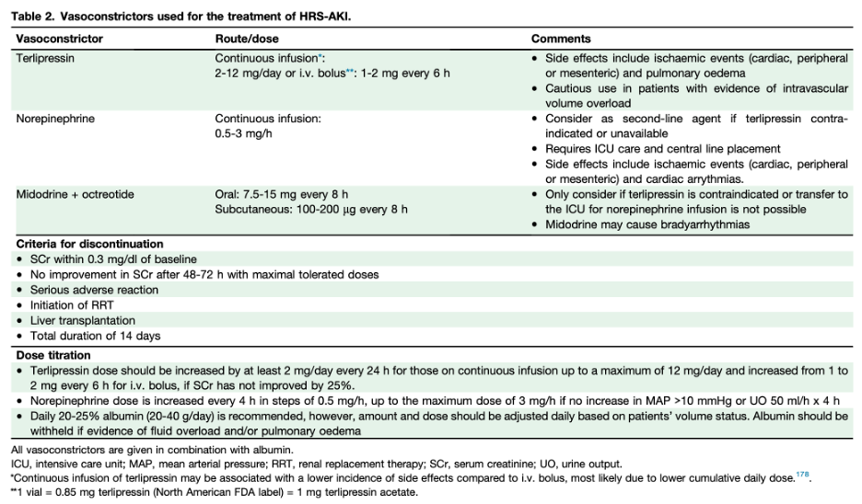

Therefore, in institutions where terlipressin is not available or when there are substantial contraindications (hypoxia, advanced acute-on-chronic liver failure, ischemic heart disease or other hospital-specific guidelines), the recommendation is to transfer patients to the intensive care unit for NE treatment, using midodrine in combination with octreotide until NE can be administered.

Once the appropriate vasoconstrictor has been selected, the next priority is to target an aggressive mean arterial pressure (MAP) goal (dosing and comments in table at end). A practical target is to increase MAP by more than 10 mm Hg within 3 days of therapy initiation, as data suggest an inverse relationship between MAP elevation and serum creatinine levels.

Simultaneously, although all vasoconstrictor therapies require albumin administration, the patient’s intravascular status must be carefully assessed, and albumin use should be tailored accordingly. The ADQI and ICA recommend a one-day volume challenge with either 250–500 mL of crystalloid or 1–1.5 g/kg of 20–25% albumin, with HRS-AKI diagnosed if creatinine or urine output does not improve within 24 hours.

While a short volume challenge is recommended to prevent delays in therapy, indiscriminate albumin administration can be harmful to certain patients. For instance, in a study involving 126 cirrhotic patients undergoing right heart catheterization for transplant evaluation, 62% had elevated filling pressures, and many improved after switching from triple therapy (midodrine, octreotide, and albumin) to diuretics—indicating that their kidney dysfunction was due to cardiorenal physiology rather than HRS. For clinicians skilled in point-of-care ultrasound, the VEXUS score can help further assess volume status and differentiate cardiorenal syndrome from HRS at the bedside.

Lastly, unless contraindications exist, patients with HRS-AKI should be considered for liver transplantation. Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment as it addresses the underlying pathophysiology of liver failure and portal hypertension.

Vasoconstrictor doses and considerations from 2024 ADQI-ICA consensus.

Overview of trials in HRS from the Velez review: