Renal artery stenosis (RAS) can lead to a reduction in kidney blood flow with resultant ischemia of the affected kidney. The consequences of this reduction are a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with the development of renovascular hypertension. Historically, stenting of RAS was believed to reverse the decreased blood flow and lessen the activation of the RAAS. The most common cause of RAS is atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (ARAS), which is responsible for up to 90% of the cases of renovascular disease. Below we will describe the landmark trials that have guided us to our current belief in optimal treatment for our patients with RAS

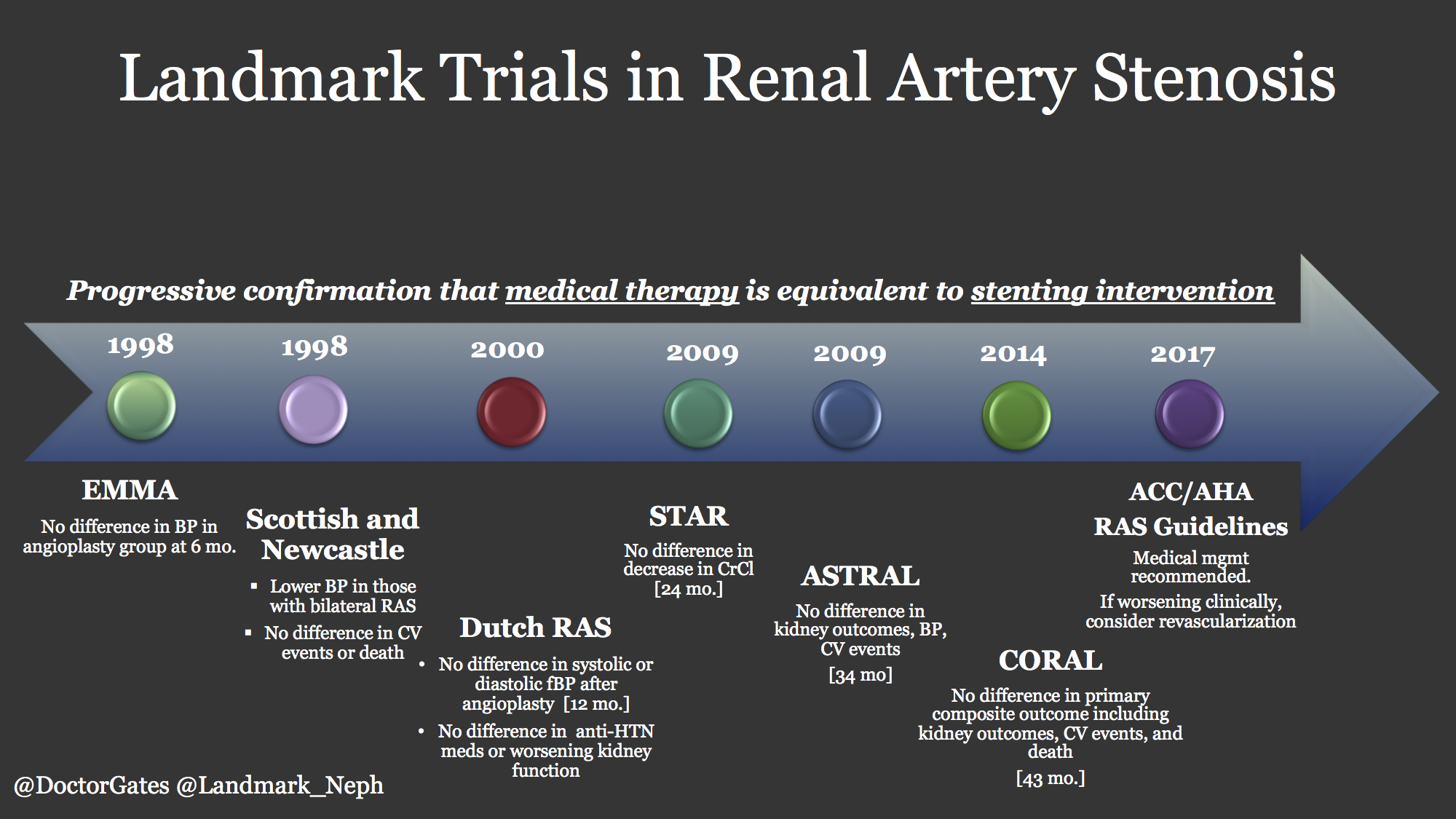

A few small randomized trials began in the late 1990’s to determine a competitive advantage of angioplasty for RAS. The EMMA study group looked at 49 total patients, but was not able to find any improvements with angioplasty at six months. Similarly the Scottish and Newcastle collaborative group in the same year did not find any difference with angioplasty in a total cohort of 135 patients with the longest follow up of 54 months. A Dutch group as well looked at 106 patients split into medical therapy versus angioplasty and duplicated the results of no difference at 12 months in systolic pressure, medication use, or decreased kidney function. All of these trials had limitations of short time frames, high (29% average) crossover rate, and small cohorts that may have lacked power to adequately determine differentiation.

Let’s review three important randomized trials below.

1. STAR 2009

The beginning of quality randomized clinical trials looking at RAS began in 2009. The STAR trial was published in the Annals which included a randomized cohort based in the Netherlands and France examining 140 patients with eGFR <80 mL/min/1.73 m2, stable blood pressure <140/90 mmHg, and ostial RAS of at least 50% stenosis. These patients were randomized to aggressive medical therapy including anti-hypertensive agents, atorvastatin, and aspirin, or to the same medical therapy along with stenting. After 24 months, the authors did not find a significant difference between the groups (primary outcome: a 20% or greater decrease in creatinine clearance). Ten of the 64 patients (16%) in the stent placement group and 16 patients (22%) in the medical treatment only group reached the primary end point (hazard ratio, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.33 to 1.61]. The trial had limitations with 25% of the stenting arm that never actually received a stent. The STAR trial was criticized for its small cohort and exclusion of high risk RAS patient as it is recognized that decreased kidney blood flow and clinical consequences of RAS do not occur until there is greater than 70-80% lumen narrowing.

2. ASTRAL

Also published in 2009, this trial was larger in size than STAR with enrollment including 806 patients. After a mean follow up of 34 months, there was no significant difference in kidney outcomes, blood pressure control, or cardiovascular events (p=0.06). This study had several limitations as well. Not only did 40% of enrollees have < 70% stenosis, but 25% had normal eGFR who would be considered very low risk status and likely not have any benefit from stenting in the first place. The major criticism of ASTRAL was allowing physicians to only enroll patients if they felt that revascularization would be beneficial. Because of a lack of equipoise there was a clear recruitment bias as evidenced by the low rate of randomization of otherwise eligible patients. As with the STAR trial, ASTRAL was criticized for not including enough high-risk patients who would benefit from revascularization.

3. CORAL

The largest RAS trial to date with comparison of cardiovascular and kidney events in patients with ARAS was the Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial published in NEJM 2014. This trial was devised to try and solve some of the limitations and criticisms of the previous studies. A large cohort of 947 patients was included and all had a systolic blood pressure > 155 mmHg, were on more than two anti-hypertensive medications, and had an eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.72 m2. The patients were randomized to medical therapy, or stenting with medical therapy, for a median of 43 months. The primary endpoint was a composite of death from cardiovascular or renal causes, stroke, myocardial infarction hospitalization for congestive heart failure, progressive loss of eGFR, or need for permanent dialysis. The trial was longer than both STAR and ASTRAL and contained a higher risk population, eliminating criticisms seen in previous cohorts. Despite even more comprehensive clinical enrollment criteria, there was no difference in occurrence of the primary composite endpoint or any individual components. The only significant finding was lower systolic blood pressure in the stenting arm at the end of the trial (95% CI; p=0.03). A correspondence in NEJM was published four months later that looked at patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

When examining the three randomized trials of STAR, ASTRAL and CORAL, there was no significant evidence of benefit in revascularization with stenting in those with ARAS. All three trials have been criticized for not including enough high-risk patients.

Additionally, almost all the patients had hypertension and/or chronic kidney disease. Unfortunately, it would not be expected that revascularization would improve blood pressure or reverse renal disease in these individuals given the extent of their disease states and morbidity. As well, it is not surprising that revascularization of the kidney does not modify pathologic changes in other organs.

Our medical societies have also come to some recommendations based on these major trials. The 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guidelines have addressed ARAS and treatment guidance. The writers recommend at minimum all patients with ARAS should have medical therapy citing Level 1A evidence. If a patient has failed medical management and continues to have clinical evidence of refractory hypertension, worsening renal function or intractable heart failure, revascularization should be considered. ACC/AHA do not fully endorse any specific procedure or evidence of outcome benefit.

There are currently several clinical trials looking at devices and other medical treatments to help determine who should benefit from intervention.

Author: Gates Colbert, MD, FASN

Landmark Nephrology is an online learning tool designed to collect landmark trials in nephrology and distribute content that makes learning nephrology fun and easy.

Please visit us to check out our topic-specific content including videos, visual abstracts, quizzes, and a new slide-share portal to facilitate the exchange of educational material within the nephrology community.

We love collaboration so contact us as landmarknephrology@gmail.com or find us on Twitter to get involved!