Crystals are a frequent finding in the urinary sediment. Besides microcrystalline deposits (amorphous phosphates and urates), the most common types of crystals in my practice are:

1. CaOxalate dihydrate (COD)

2. CaOxalate monohydrate (COM)

3. Uric acid

4. Struvite

In their more typical forms they can be readily identified by microscopic morphology, their appearance under polarized light, and urinary pH.

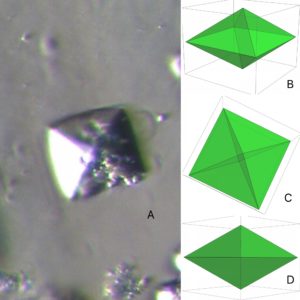

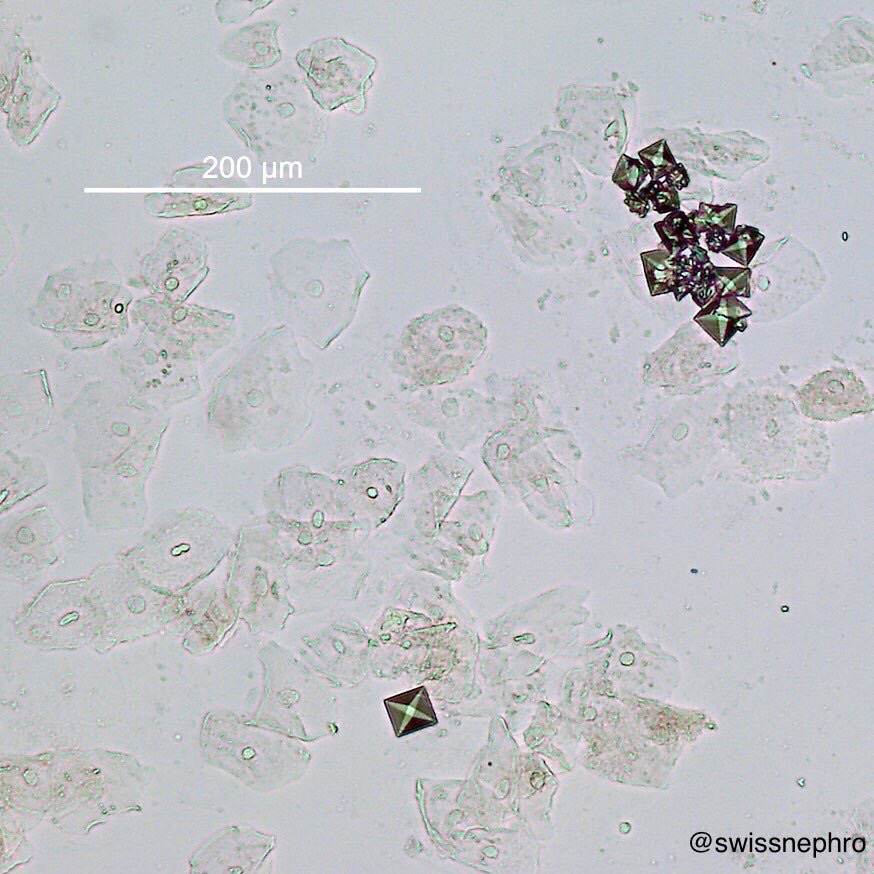

CaOxalate DiHydrate crystals: COD crystals usually display a bipyramidal structure (Fig. 1). With bright field microscopy these resemble envelopes (Fig. 1C, 2, 3), which do not exhibit any significant birefringence. They are mostly independent of urinary pH, but are less common in alkaline urine. Their clinical relevance is limited, as they are often encountered in perfectly healthy people. In contrast to COM crystals they develop in conditions with higher ratios of calcium to oxalate.

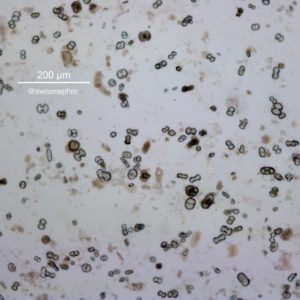

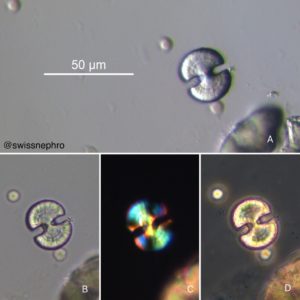

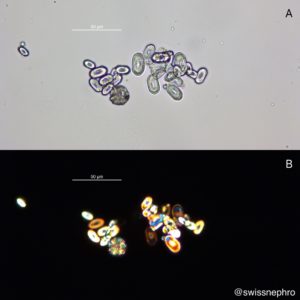

CaOxalate MonoHydrate crystals: COM crystals show a much more varied morphology. Dumbbell shapes (Fig. 4, 5) are known best, but ovoids, often with a navel, are much more common (Fig. 6). COM crystals show intense birefringence (Fig. 5C, 6B). As for COD their development is not significantly influenced by urinary pH values. Exclusive COM crystalluria should alert you to the presence of hyperoxaluric conditions.

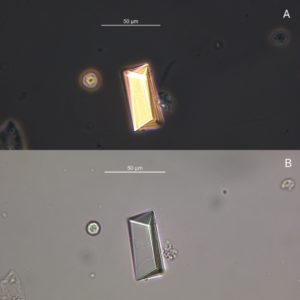

Uric acid crystals: An even wider spectrum of morphologies can be found with uric acid crystals (Fig. 7 and 8). Typical shapes include barrels, rhomboids, rosettes. They are frequently amber colored (Fig. 8) and show intense and often polychromatic birefringence (Fig. 9). Uric acid crystals are encountered in acidic urine only.

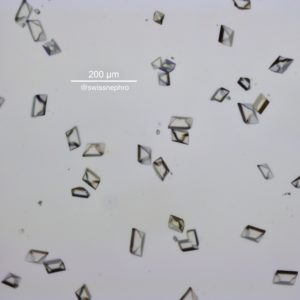

Struvite crystals: They lie at the other end of the pH spectrum and are found in alkaline urine, often due to infections with urease splitting organism. Typical crystals show a characteristic coffin-lid morphology (Fig. 10 and 11) with only weak to moderate birefringence. Somewhat tilted forms are also common (Fig. 12).

Given the wide morphological spectrum of each crystalline category, accurate classification of unusual crystals in the urinary sediment can be difficult, if possible at all. Confirmation may require more sophisticated methods like infrared spectroscopy (FTIRM).

Further reading:

1. Daudon, M., Frochot, V., Bazin, D. & Jungers, P. Crystalluria analysis improves significantly etiologic diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of nephrolithiasis. Comptes Rendus Chimie 19, 1514-1526 (2016).

2. Fogazzi, G. B. Crystalluria: a neglected aspect of urinary sediment analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11, 379-387 (1996).

3. Frochot, V. & Daudon, M. Clinical value of crystalluria and quantitative morphoconstitutional analysis of urinary calculi. Int J Surg 36, 624-632 (2016)

Post by: Florian Buchkremer

Excellent photos, Brilliant Detailing