The presence of HIV has in the past been viewed as a relative contraindication to transplantation. This stance stemmed from concerns that immunosuppression would exacerbate an already immunocompromised patient and accelerate the disease process of AIDs. Additionally, there was an ethical concern in terms of giving a precious, limited resource to a group with what was in the past considered limited life expectancy.

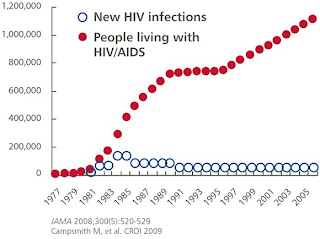

However, the widespread introduction of HAART in the mid-90s has resulted in a marked decrease in morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV. As a result, people infected with HIV are living longer and dying less often from opportunistic infections and progression to AIDS, and more often from complications of traditional comorbidities such as coronary disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. The incidence of ESRD continues to rise in those infected with HIV, and it is estimated that 1% of patients with ESRD are infected with HIV. In the United States, HIV nephropathy is the third most common cause of ESRD among blacks who are between the ages of 20 and 64.

As a result of this increasing incidence of disease and the improvement in management of HIV, many transplant centers have now eliminated HIV as a contraindication for transplantation. Several small studies have shown promising results, but there is really a lack of quality evidence in this field and it remains a controversial topic amongst nephrologists.

A recent publication in the NEJM has provided some stronger, encouraging data demonstrating that transplanting an HIV-positive recipient is feasible and offers good outcomes.

This study was a multicenter, non-randomized, prospective trial that was conducted at 19 U.S. transplant centers, which was designed to examine the safety and efficacy of kidney transplantation in ESRD patients who were also infected with HIV. The authors followed prospectively 150 HIV-positive recipients for up to 3 years after transplantation. Inclusion criteria were a CD4 count greater than 200 and undetectable viral load in the serum in the 16 weeks prior to transplantation. Patients were excluded if they had a history of PML, CNS lymphoma, or visceral kaposi’s sarcoma. They also were excluded if they did not meet center-specific transplant criteria. Primary outcomes were patient and allograft survival, and secondary outcomes were opportunistic complications, changes in CD4 counts, and detectable plasma HIV RNA levels. Refer to the paper for further details on their methods and post-transplant care.

The authors looked at patient and graft survival rates at years 1 and 3, and compared them to both the survival rates reported by the scientific registry of transplant recipients (SRTR) for all kidney transplant recipients, as well those older than 65. They conclude that patient survival rates in their population were similar to that of the general population, and that allograft survival rates were somewhere between that of the general population and the high risk elderly population. Significant opportunistic infections were minimal and there was no evidence of HIV progression during their follow period. Neoplasm rates were comparable to the general population, and there were no cases of PTLD. Interestingly, as has been previously described, they found their patients to have a very high rate of acute rejection which is much higher than the general population.

While this study does have its limitations, it provides some convincing evidence supporting kidney transplantation in HIV-infected patients. In a carefully selected population of HIV-infected patients with ESRD, it shows that kidney transplantation is a safe and feasible management option.

Justin Westervelt, MD