Her serum creatinine was 0.8 mg/dl and her albumin was 1.6 g/dl. Her serologies were entirely negative. The protein/creatinine ratio was 6 and 9 on two occasions. The presumptive diagnosis was IgA nephropathy and she proceeded to a renal biopsy.

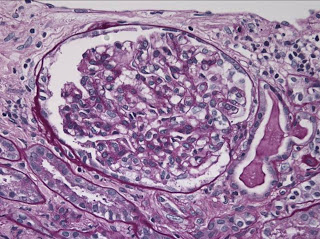

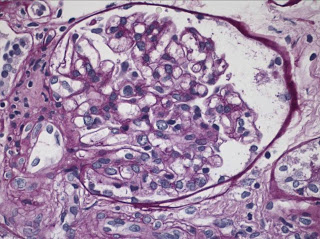

Low power view of the renal cortex showed mild chronic parenchymal changes that would not be unusual for someone of her age – 2/20 glomeruli were sclerosed and there was focal tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis affecting less than 5 percent of the parenchyma

Her glomeruli looked normal with no evidence of inflammation or mesangial expansion.

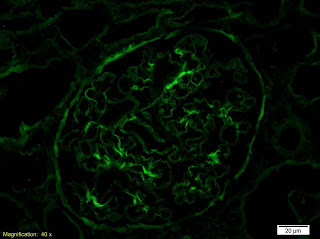

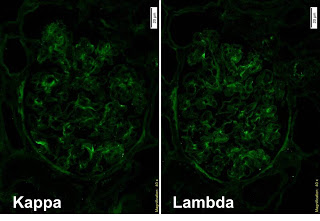

There was no staining for IgA. There was minimal IgG staining with equal kappa and lamda.

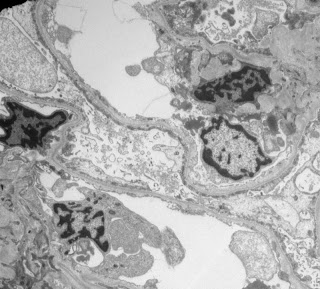

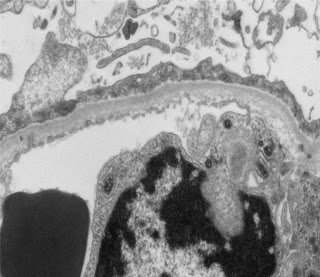

EM showed diffuse effacement of the foot processes consistent with minimal change disease. But, why did she have hematuria?

The answer is revealed by looking closer at the basement membranes. The harmonic mean thickness of the BM was 196nm which is diagnostic for thin basement membrane disease. The hematuria in this case was a red herring – her acute diagnosis was minimal change disease and she simply had not previously been noted to have hematuria.

TBMN is the commonest cause of persistent hematuria, present in about 1% of the population. It has a benign prognosis and is associated with a positive family history. It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from forms of Alport’s syndrome early in the course of the disease. It results from heterozygous mutations in the COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes. Interestingly, the penetrance of hematuria is only 70% so the absence of a positive family history of hematuria does not definitiely suggest a de novo mutation. Episodes of macrosopic hematuria can follow an acute infection and thus mimic IgA although this is relatively rare. One of the bigger issues is making the diagnosis and criteria and measurement techniques vary by institution.

There is no specific treatment required although patients do need to be followed up as there are some atypical cases of Alport’s syndrome which can present similarly but are associated with progression. Some have advocated treating patients with ACEi to prevent episodes of hematuria but the evidence for this is not strong. Patients with TBMN can be kidney donors although they should have a renal biopsy first to make certain that there is no other diagnosis. Here is an excellent review from 2006 and more recently, expert guidelines on the management of Alport’s and TBMN were published in JASN.