A 42-year-old man developed AKI during his recent hospitalization due to presumed sepsis. He was started on vancomycin and levofloxacin as empirical therapy. When renal was consulted 7 days after admission, creatinine level had peaked at 4.39 mg/dl and WBC 33K with eosinophilia. Urinalysis was associated with 2+ proteinuria and 2+ leukocyte esterase with some granular casts, though no cellular casts were visualized. On examination, he had generalized erythematous rash associated with diffuse body edema.

The initial diagnosis by the team was thought to be ATN associated with sepsis, though the presence of rash and eosinophilia raised the concern for superimposed drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).

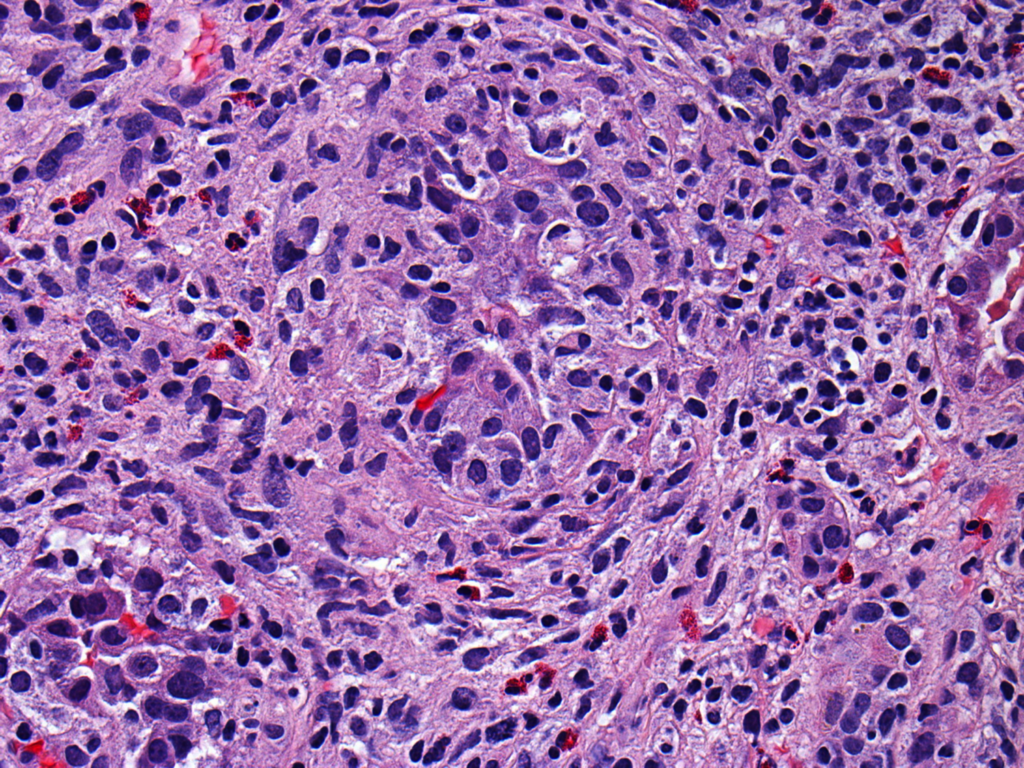

A renal biopsy was performed and the histopathologic findings revealed an AIN with granulomatous features (figure on the top left – Courtesy of Dr Rennke/Dr Bijol).

AIN is a common finding in kidney biopsies of patients with acute renal failure in the hospital. However, granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) occurs in only about 1% of biopsies.

GIN is a histologic form of interstitial nephritis characterized by the presence of necrotizing or non-necrotizing granulomas in renal biopsy. Its pathogenesis is not well defined. Some immunologic mechanisms were proposed as culprits such as T-cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity, anti-tubular basement membrane antibodies and autoimmune antibody response.

Potential etiologies include:

– Drug-induced processes [[most common]] (Antibiotics, NSAIDs, Diuretics (thiazide), Allopurinol, Anticonvulsant (lamotrigine), Omeprazole, Bisphosphonate, All-trans retinoic acid, Heroin abuse)

– Infections (xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections; Histoplasmosis and other fungal infections; adenovirus)

– Systemic inflammatory conditions (Sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, TINU, Crohn’s disease)

In about 15% of cases, an exact etiology for GIN is not found.

Further work-up on the case above did not reveal any systemic inflammatory process or infections, though a high suspicion for antibiotic-induced GIN was raised. In particular, there has been case reports of levofloxacin-associated GIN.

The treatment of GIN depend on the underlying associated factor. For example, in drug-induced processes, the removal the offending agent will play a central role in the treatment; while in infection-related cases, the underlying infection must be controlled.

In the case presented, antibiotics were changed and an empirical trial of steroids was administered. Patient’s creatinine slowly trended down in the subsequent weeks but plateau at 1.5 mg/dl. Though there has been no randomized trials, most GIN cases deserve a trial of steroids once infectious etiologies are excluded, in particular based on the intense inflammation observed on the biopsies.

I was diagnosed with GIN in February of 2015. No obvious cause, thought to be autoimmune. Lots of prednisone lowered creatinine levels to 1.2-1.5. Currently take 2.5 mg of pred every other day. Female, healthy, fit, 56 at time of diagnosis.

What about the side effects of the steroids treatment and the continued body pain that the patient suffers? My mom cannot walk for long or do much of any physical activity since she was treated.

Now her creatinine ranges between 1 and 1.4.