PART 3: THE DANGERS

OF “DEPLETION”

OF “DEPLETION”

In my previous post concerning chronic severe hyponatremia,

I explained how over corrections of serum sodium of large magnitude required a

dilute large volume diuresis, often precipitated by resolution of a transient

source of ADH secretion. In this post I

will discuss two phenomena which are particularly dangerous as they carry

significant risk of producing large volume water diuresis.

I explained how over corrections of serum sodium of large magnitude required a

dilute large volume diuresis, often precipitated by resolution of a transient

source of ADH secretion. In this post I

will discuss two phenomena which are particularly dangerous as they carry

significant risk of producing large volume water diuresis.

1. Subclinical Volume Depletion: As

mentioned in my previous post, we noticed during our review of a large number

of cases of severe hyponatremia treated with 3% saline that most of the

patients whose serum sodium eventually overcorrected responded to small volumes

of 3% saline as if they were volume depleted, with sudden emergence of water

diuresis. Interestingly, most of these

patients were initially considered to be euvolemic by experienced

nephrologists.

mentioned in my previous post, we noticed during our review of a large number

of cases of severe hyponatremia treated with 3% saline that most of the

patients whose serum sodium eventually overcorrected responded to small volumes

of 3% saline as if they were volume depleted, with sudden emergence of water

diuresis. Interestingly, most of these

patients were initially considered to be euvolemic by experienced

nephrologists.

This very interesting paper reviewed the literature

concerning the value of physical examination in diagnosing volume

depletion. The conclusion, rather

humbling, was that other than in cases of severe volume depletion our physical

exam was quite inaccurate in diagnosing volume depletion. This is especially concerning considering

that establishing a patient’s volume

status forms the major decision point in the ubiquitous diagnostic algorithm

for hyponatremia.

concerning the value of physical examination in diagnosing volume

depletion. The conclusion, rather

humbling, was that other than in cases of severe volume depletion our physical

exam was quite inaccurate in diagnosing volume depletion. This is especially concerning considering

that establishing a patient’s volume

status forms the major decision point in the ubiquitous diagnostic algorithm

for hyponatremia.

According to the paper, reliable signs of volume depletion

usually are visible with the loss of about 20% of the intravascular

volume. The ADH secretion and response

to volume depletion starts with volume losses as low as 5-8% of the effective

intravascular volume. This implies that

the patient may have significant ADH secretion, contributing to the relative

excess water retention causing hyponatremia, while clinically appearing

euvolemic. It also means small volume

bolus may switch off this ADH secretion, causing water diuresis and sudden rise

in serum sodium.

usually are visible with the loss of about 20% of the intravascular

volume. The ADH secretion and response

to volume depletion starts with volume losses as low as 5-8% of the effective

intravascular volume. This implies that

the patient may have significant ADH secretion, contributing to the relative

excess water retention causing hyponatremia, while clinically appearing

euvolemic. It also means small volume

bolus may switch off this ADH secretion, causing water diuresis and sudden rise

in serum sodium.

Subclinical volume depletion as a contributor to

hyponatremia should always be considered a possibility especially when starting

therapy with 3% saline.

hyponatremia should always be considered a possibility especially when starting

therapy with 3% saline.

2. Solute Depletion Hyponatremia: The so

called “Tea and Toast Diet ” hyponatremia and “Beer

Potomania” are examples of solute depletion hyponatremia. As nicely described by Dr. Berl, our solute intake limits our ability to excrete free water. Even with a maximally dilute urine of around

50 mOsm/L, a person consuming a 300 mOsm/d diet can only excrete 6 L of urine

(300/50=6). Such a person will become

hyponatremic with drinking more than 6 L of fluids a day because any water in

excess of 6 L per day excretory capacity will be retained in the body. It is important to note that this water

retention is not due to ADH secretion.

ADH is often suppressed in such patients. The renal danger of this pathophysiological

mechanism is that whenever such patient is “presented” with solute

(IV normal saline, high-protein meal which would generate BUN or even 3%

saline!), without a high ADH level to prevent it, the added solute is used to

rapidly excrete free water that has been “trapped” in the body.

called “Tea and Toast Diet ” hyponatremia and “Beer

Potomania” are examples of solute depletion hyponatremia. As nicely described by Dr. Berl, our solute intake limits our ability to excrete free water. Even with a maximally dilute urine of around

50 mOsm/L, a person consuming a 300 mOsm/d diet can only excrete 6 L of urine

(300/50=6). Such a person will become

hyponatremic with drinking more than 6 L of fluids a day because any water in

excess of 6 L per day excretory capacity will be retained in the body. It is important to note that this water

retention is not due to ADH secretion.

ADH is often suppressed in such patients. The renal danger of this pathophysiological

mechanism is that whenever such patient is “presented” with solute

(IV normal saline, high-protein meal which would generate BUN or even 3%

saline!), without a high ADH level to prevent it, the added solute is used to

rapidly excrete free water that has been “trapped” in the body.

As an example, consider the case of the 26-year-old female

that I briefly alluded to in the previous post.

She presented with a serum sodium of 108 mEq/L after being on an

exclusively alcohol diet for the last 2 weeks.

She received 2 L of normal saline in the ER (154 mEq x2 = 308 mEq of

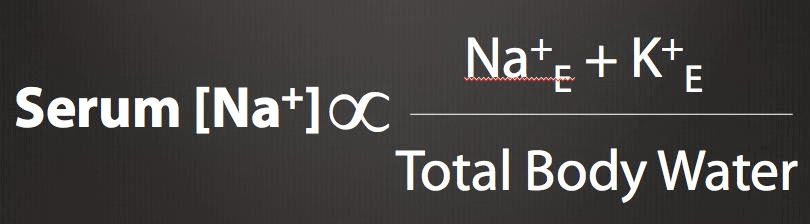

Na). Using the Edelman equation (see figure) and an initial total body water of

32 L, if we do not account for urine output, that amount of added NaCl would

have raised the serum sodium to about 111 mEq/L. But the actual rise of serum

sodium was to 131 mEq/L in about 5 hours accompanied by almost 7 liters of dilute

urine output. Her kidneys used the roughly 300 mEq of sodium in the NS bolus to

excrete more than 6 liters of maximally dilute urine (300/50=6 L, remember the

earlier calculation?) and almost perfectly accounts for the 23 mEq/L rise in

serum sodium (by reducing the denominator, TBW).

that I briefly alluded to in the previous post.

She presented with a serum sodium of 108 mEq/L after being on an

exclusively alcohol diet for the last 2 weeks.

She received 2 L of normal saline in the ER (154 mEq x2 = 308 mEq of

Na). Using the Edelman equation (see figure) and an initial total body water of

32 L, if we do not account for urine output, that amount of added NaCl would

have raised the serum sodium to about 111 mEq/L. But the actual rise of serum

sodium was to 131 mEq/L in about 5 hours accompanied by almost 7 liters of dilute

urine output. Her kidneys used the roughly 300 mEq of sodium in the NS bolus to

excrete more than 6 liters of maximally dilute urine (300/50=6 L, remember the

earlier calculation?) and almost perfectly accounts for the 23 mEq/L rise in

serum sodium (by reducing the denominator, TBW).

This would have also happened if she had received the same

amount of NaCl in the form of 3% saline as in such cases the volume of infusate

matters less than the amount of solute delivered.

amount of NaCl in the form of 3% saline as in such cases the volume of infusate

matters less than the amount of solute delivered.

I hope this case illustrates how dangerous solute depletion

hyponatremia can be and how easy it can be to precipitate an overcorrection of

serum sodium in such patients. This raises a very important question: if even

treatment with 3% saline is so unreliable in patients with chronic severe

solute depletion hyponatremia, how can we safely treat such patients? That will

be the subject of my next post.

hyponatremia can be and how easy it can be to precipitate an overcorrection of

serum sodium in such patients. This raises a very important question: if even

treatment with 3% saline is so unreliable in patients with chronic severe

solute depletion hyponatremia, how can we safely treat such patients? That will

be the subject of my next post.

In conclusion, subclinical volume depletion and solute

depletion pose a particularly tricky challenge in the management of chronic

hyponatremia as sudden rises in serum sodium level can happen rather easily in

these patients with, what would otherwise seem to be, rather innocuous

treatment with saline solutions.

depletion pose a particularly tricky challenge in the management of chronic

hyponatremia as sudden rises in serum sodium level can happen rather easily in

these patients with, what would otherwise seem to be, rather innocuous

treatment with saline solutions.

Posted by Hashim Mohmand

hiya, may i know what paper regarding about the clinical assessment of volume depletion? would like to have a good read

Great post about a really interesting topic!

One slight comment, though: Could you add the link to the paper mentioned (about the difficulty of assessing volume status)? That'll be great!