Demographics

- Membranous nephropathy (MN) is one of the most common causes of nephrotic syndrome in Caucasian adults above 40 years. However, it can occur in different ages and ethnicities.

- The incidence was estimated about 8-10 cases per one million.

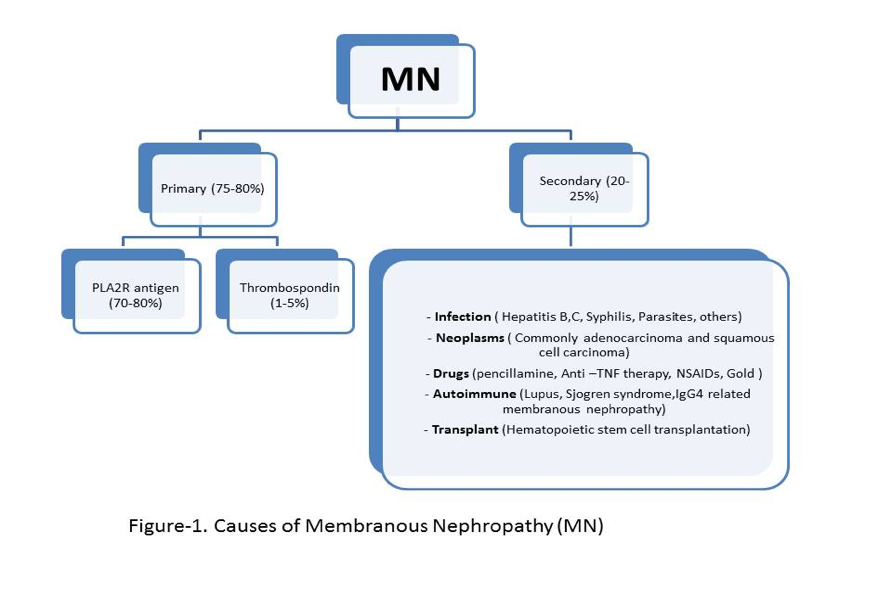

- Discovery of M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) antibodies , thrombospondin type 1 domain-containing 7A antibodies and recently EXT1/EXT2 antibodies has given new perspectives in understanding the pathogenesis of the disease process. Serum anti-PLA2R antibody (PLA2R) is the first sensitive serologic marker that has been used as a tool to prognosticate the course of the disease, in addition of its diagnostic value.

- Patients with MN have a higher incidence of renal vein thrombosis, presumably due to hypercoagulable state in the setting of nephrotic syndrome.

- It could be primary or secondary ( Figure-1)

Pathogenesis

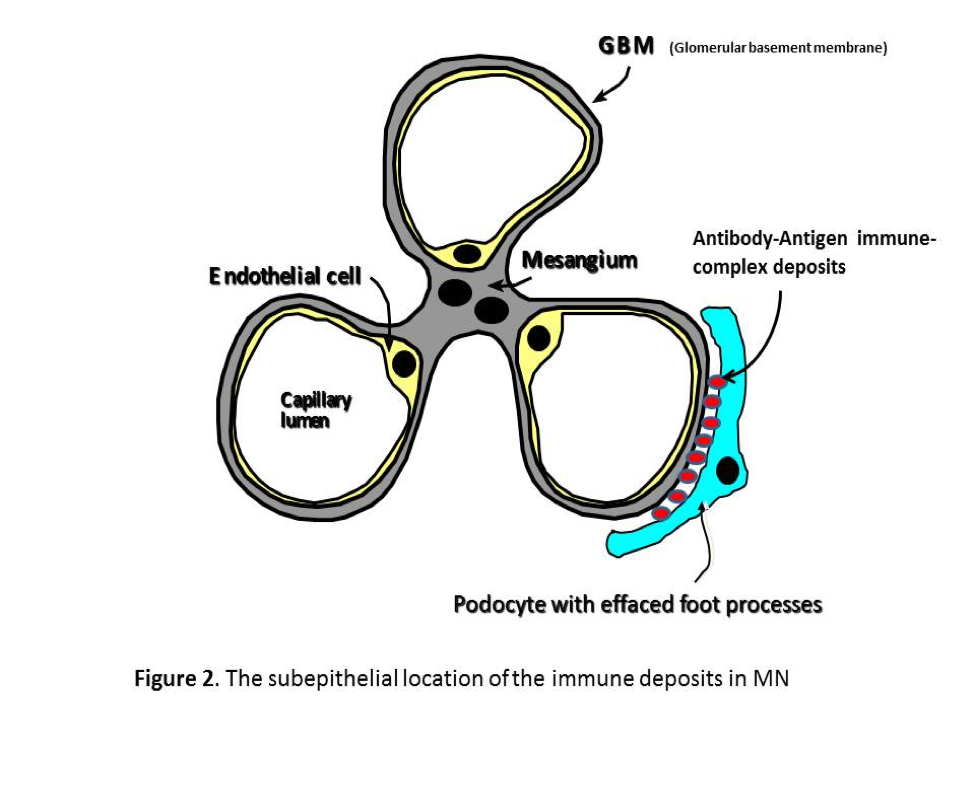

- Membranous nephropathy is caused by deposition of antibody- antigen immune complexes beneath epithelial podocyte and on the outer surface or/ and inside the glomerular basement membrane (GBM)( Figure 2 ).

- Immune complexes contain IgG, often IgG4 ( more often in primary etiology rather than secondary), and the membrane attack complex C5b-9.

- Proteinuria is a consequence of complement activation, and sublytic amounts of C5b-9 complex are incorporated into the cell membranes of podocytes, stimulating the podocytes to up-regulate genes that are responsible for the increased production of oxidants, proteases, prostanoids, cytokines, and extracellular matrix components. C5b-9 also alters the podocyte cytoskeleton, which can lead to the abnormal distribution of slit diaphragm proteins and to the detachment of podocytes into Bowman’s space. These processes impair the function of the GBM and podocytes as a filtration barrier and leads to proteinuria

Clinical Presentation

- The patients usually present with nephrotic syndrome with heavy proteinuria in more than 80%.

- Hypertension in 30% of cases.

- Hematuria in 50% of cases.

- Occasionally, the patients present with signs and symptoms of renal vein thrombosis.

Lab Testing

- Regular

blood and urine lab tests should be performed first to evaluate renal functions

and the degree of proteinuria. Additionally, other tests should be considered

to complete the full picture of the evaluation. These tests include:

- Antinuclear antibodies, complement C3, C4. These are normal in primary MN. Low complement levels are suggestive of other glomerulopathies.

- Hepatitis B and C serologies. Positive serology might suggest secondary MN.

- Age appropriate cancer screening as the malignancies are known triggers for secondary MN.

- Select patients with rapid worsening of renal function may need renal vein Dopplers, CT with contrast or MR angiography scans to look for renal vein thrombosis.

- Renal biopsy with light, immune fluorescence and electron microscopy.

- Serum level of PLA2R1 antibody.

Light Microscopy

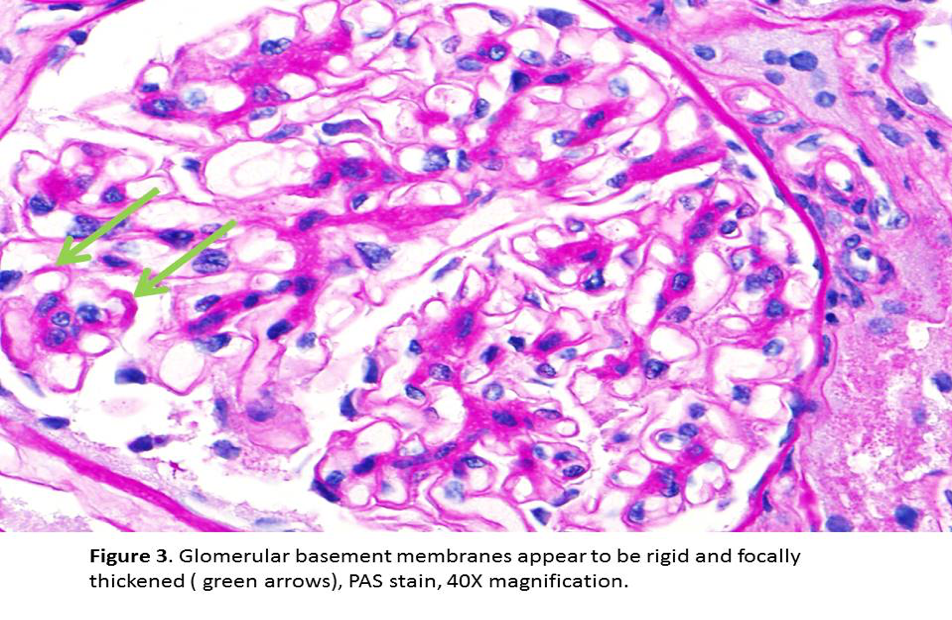

- Early MN might show no significant pathologic changes on light microscopy.

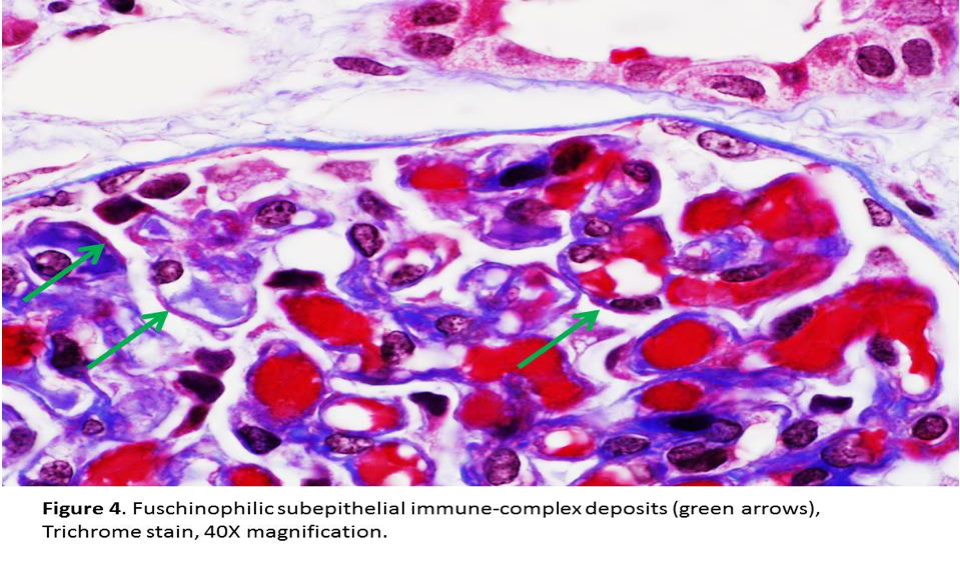

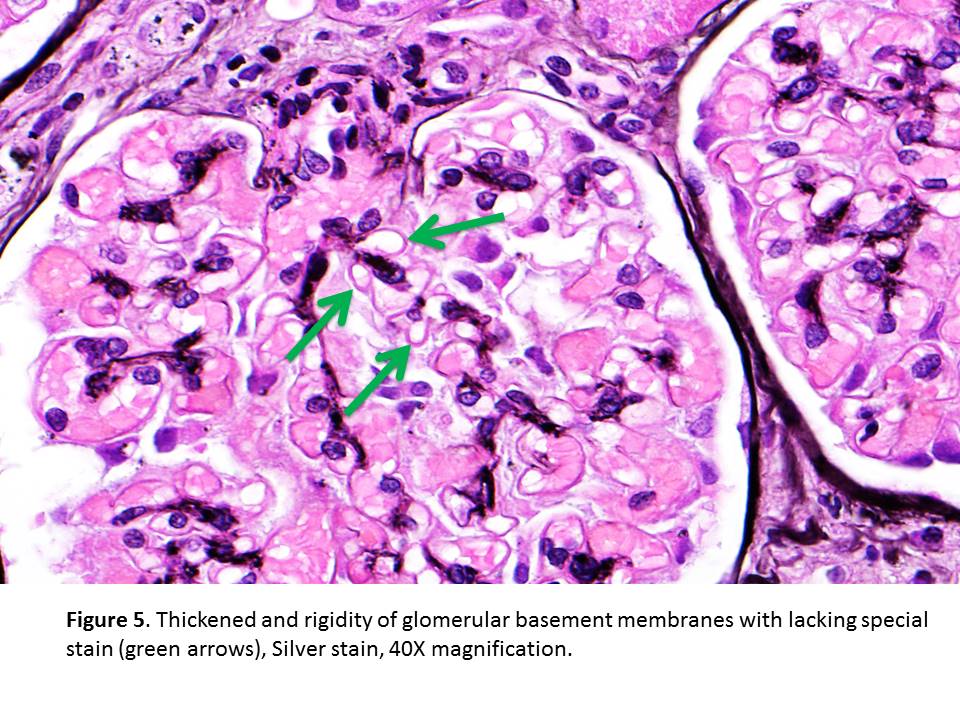

- Later stages are characterized by homogeneous thickening of GBM with “spikes” or “corrugated” texture seen in sliver stain. The deposits are light pink on the Jones silver stain and bright red on the trichrome stain (Figures 3, 4 & 5).

- Later on, lucencies may develop in GBMs as the immune deposits are resorbed. There is no conspicuous proliferation of resident glomerular cells or glomerular infiltration by inflammatory cells.

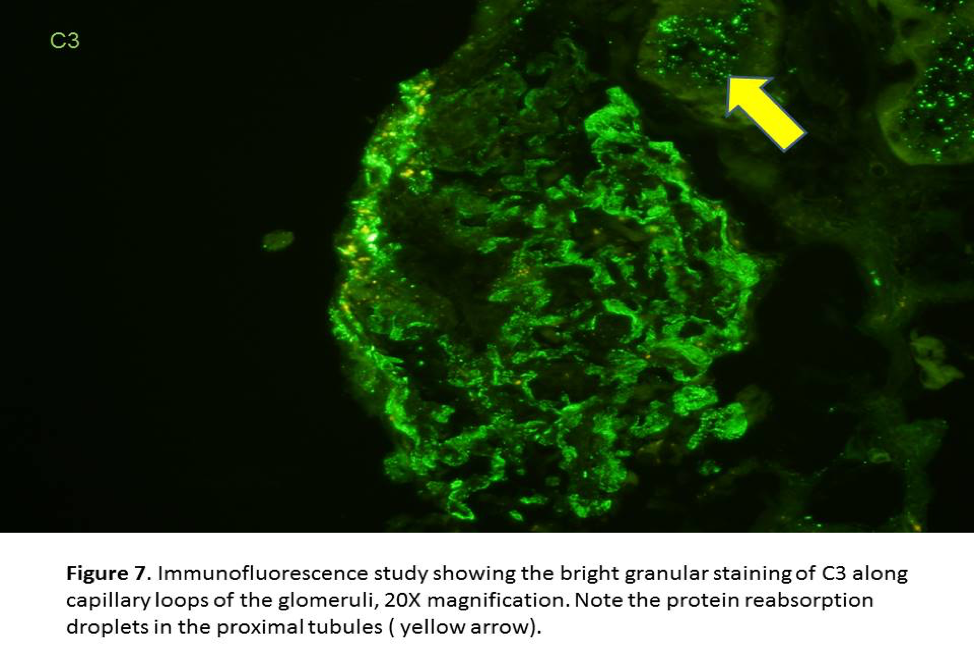

- Protein reabsorption droplets are found in the epithelial cells of proximal tubules when heavy proteinuria is present. Interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and arteriolosclerosis develop in chronic cases.

Immunofluorescence Studies

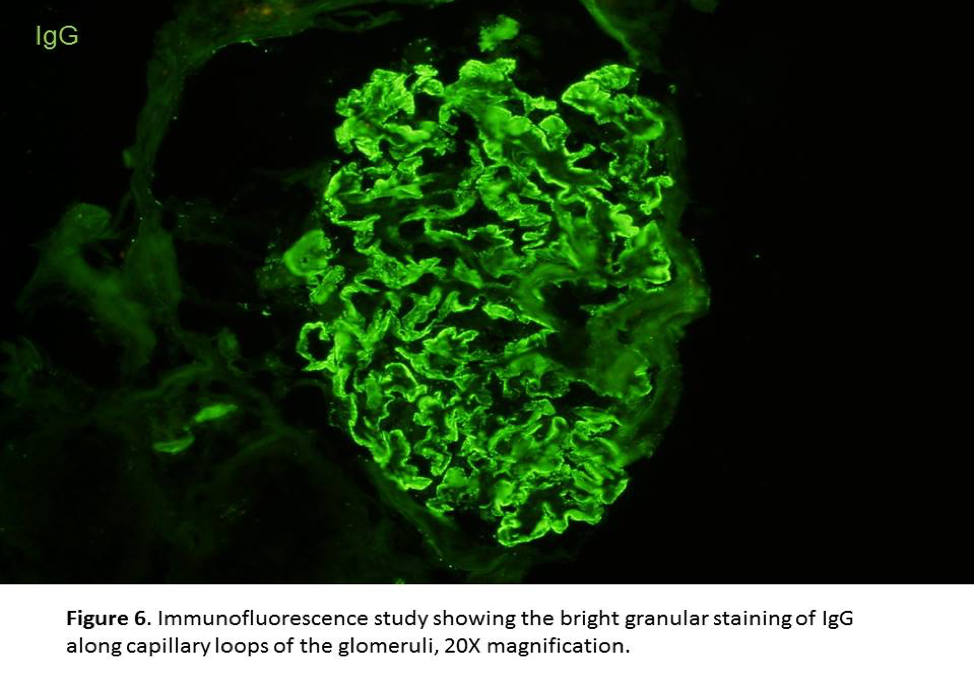

- Diffuse, granular staining for IgG and C3 along the glomerular capillary loops in subepithelial location is easily to recognize (Figures 6&7).

- IgG4 is the predominant subclass in primary MN. However, other subclasses or a ‘full house’ pattern with additional IgA, IgM and C1q staining suggests secondary MN

- Positive staining of GBM for C4d with negative C1q staining is also a feature of primary MN and is due to activation of the mannose-binding lectin pathway of complement.

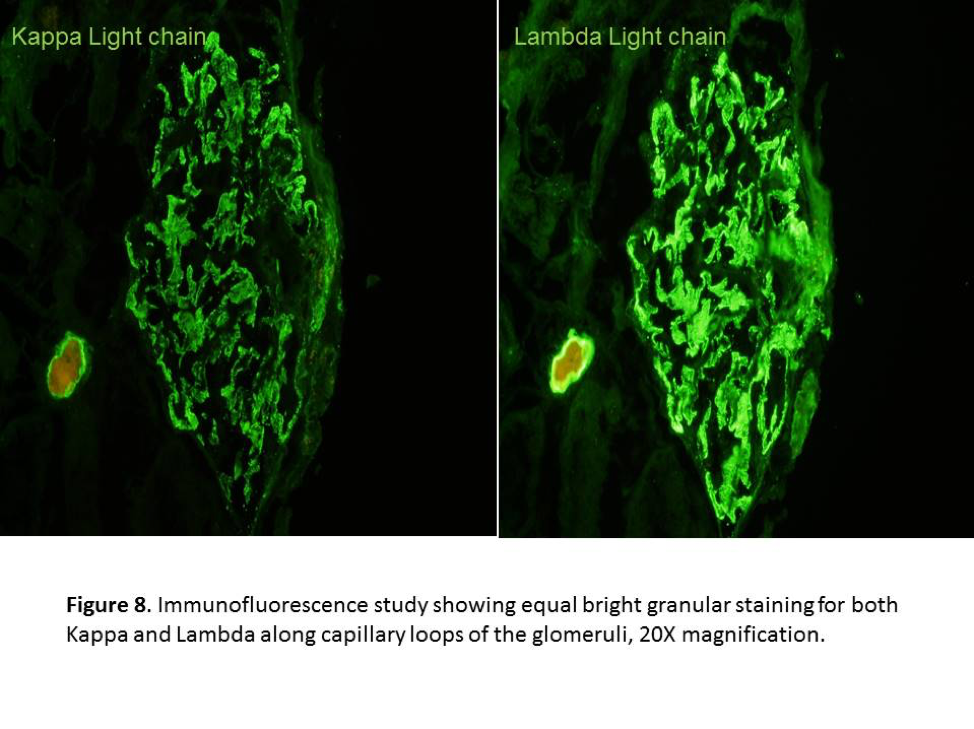

- Kappa and Lambda light chains are also stained in similar way to IgG (Figure 8).

- PLA2R staining is also in similar way with IgG deposits in primary MN positive for PLA2R1 antibodies

Electron Microscopy

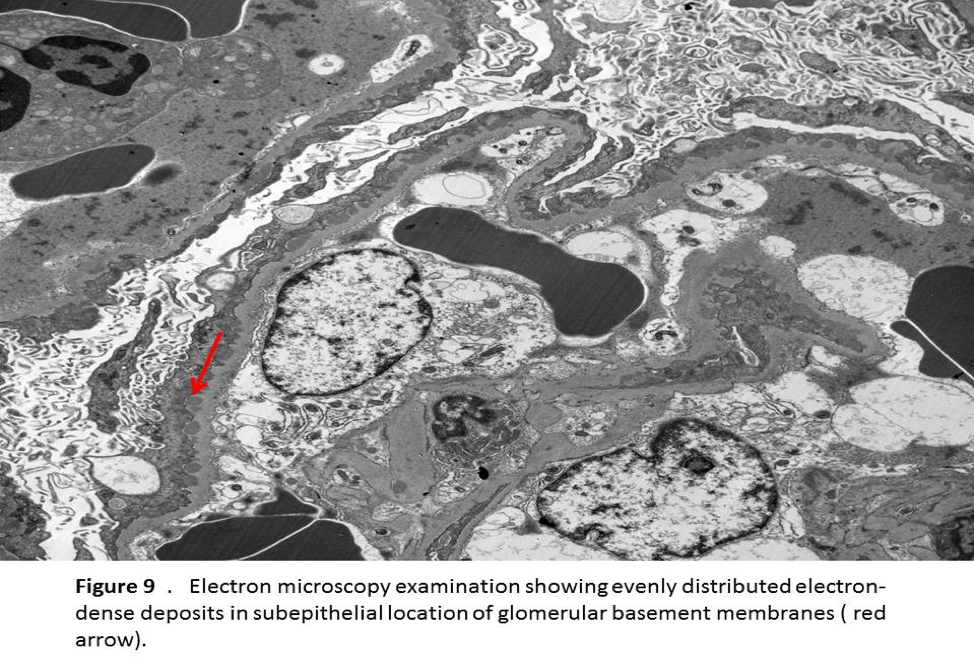

- Electron microscopy shows dense electron deposits along GBM in the subepithelial regions (Figure 9).

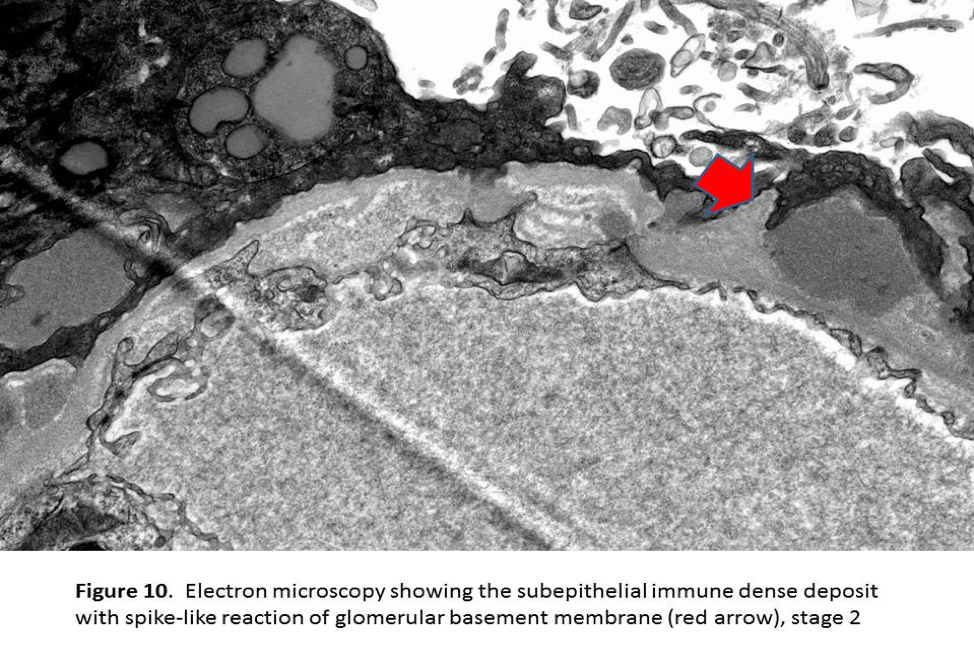

- During the early phase of MN, podocyte effacement is minimal with normal thickness of GBM (stage 1). If the deposits persist, new basement membrane material is laid between these deposits giving rise to projections formations identified on silver stains (Spikes and pinholes) which are readily observed on electron microscopy (stage 2) (Figure 10). In advanced phase of MN, these deposits are completely encased by newly laid basement membrane in intramembranous location(stage 3) . In more advanced stages, basement membranes are irregularly thickened, and the deposits become more lucent and the spikes become less apparent (stage 4).

Treatment & Prognosis

- The crucial step in the treatment MN is distinguishing between primary and secondary MN as the treatment in secondary MN is directed at the underlying etiology.

- In about 30% of cases, the spontaneous remission occurs and delay immunosuppression could be considered.

- On the other hand, 30% of patients with persistent nephrotic syndrome can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and more aggressive therapy is warranted.

- In primary MN cases, supportive therapy and targeted immunosuppression becomes the standard of care.

Sam T Albadri M.B.Ch.B, MSc.

Pathology Fellow, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota)

Thank you.