Urinary sediment microscopy is a diagnostic technique designed to acquire 2-dimensional images of structures present in a slide. However, 2-dimensional views may lack sufficient contrast to allow for optimal visualization. One way to enhance the images and create a 3-dimensional view is by applying oblique illumination.

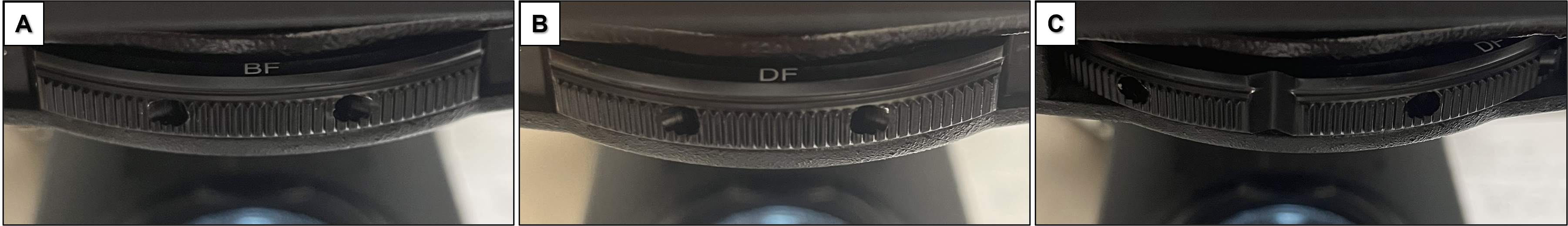

By allowing the light to project onto the field through only 1 side of the condenser, structures cast a shadow and create a 3-D-like image. Standard microscopes do not routinely come from the manufacturer set up to provide this type of illumination unless they get customized. However, oblique illumination can be easily achieved by taking advantage of the artifactual effect of partially rotating the condenser diaphragm turret between 2 fixed settings.

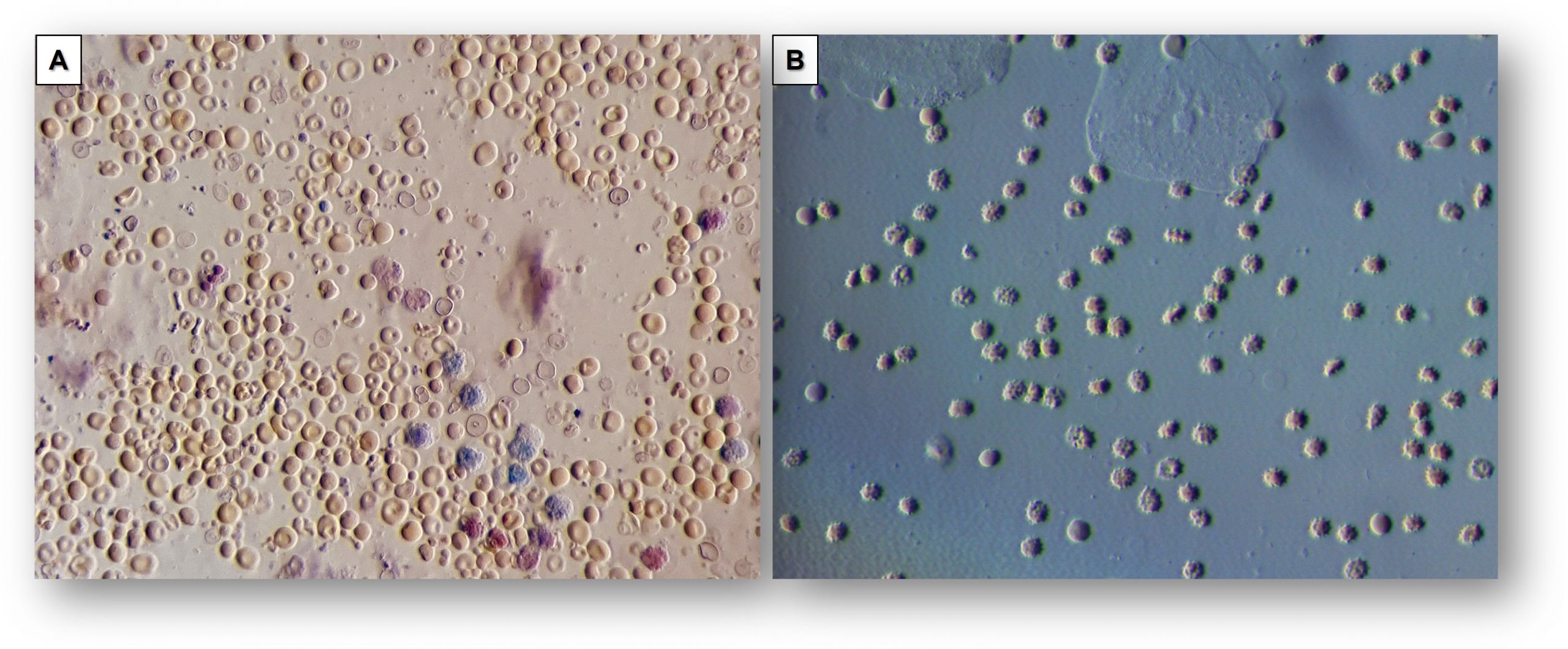

The 2 approaches that offer the best balance of light and contrast to generate a “relief” or “satellite view” effect are by rotating the condenser turret between bright field and dark field illumination (Figure 1) or between phase contrast and bright field illumination settings.

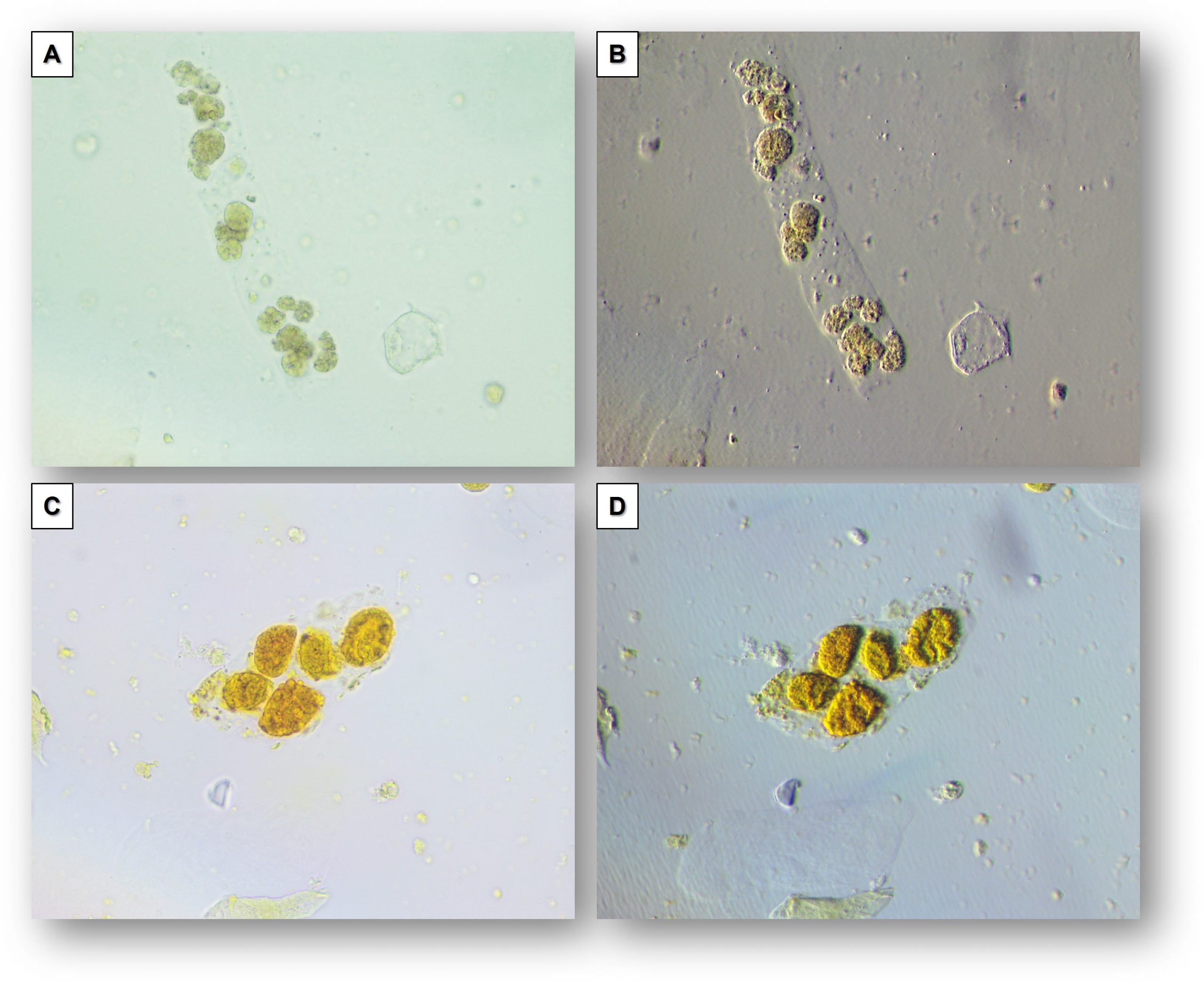

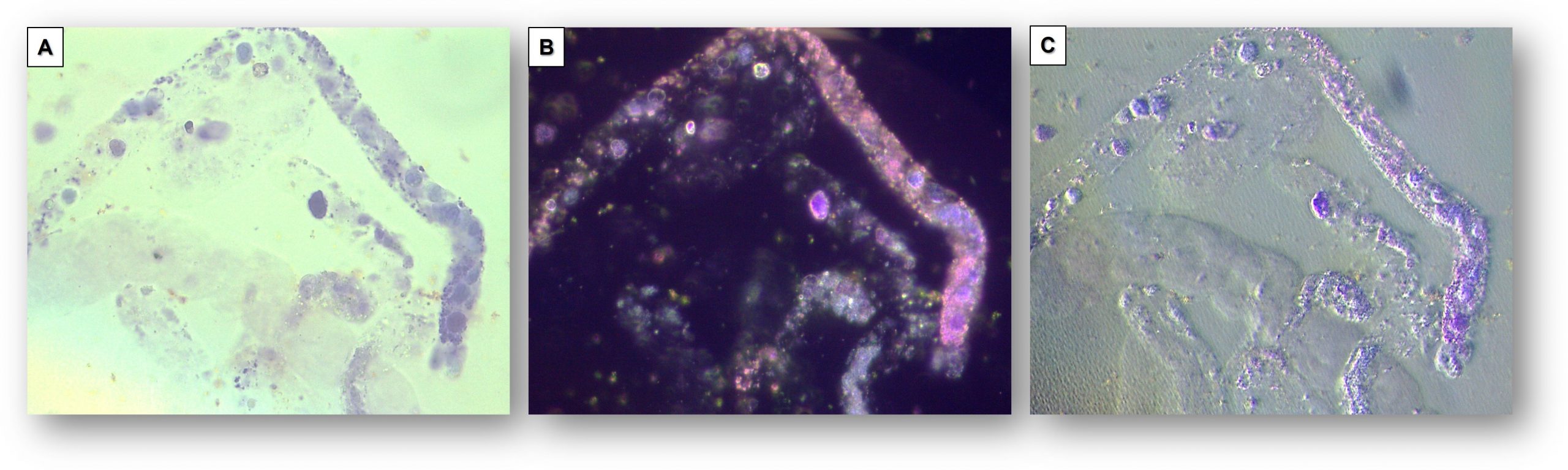

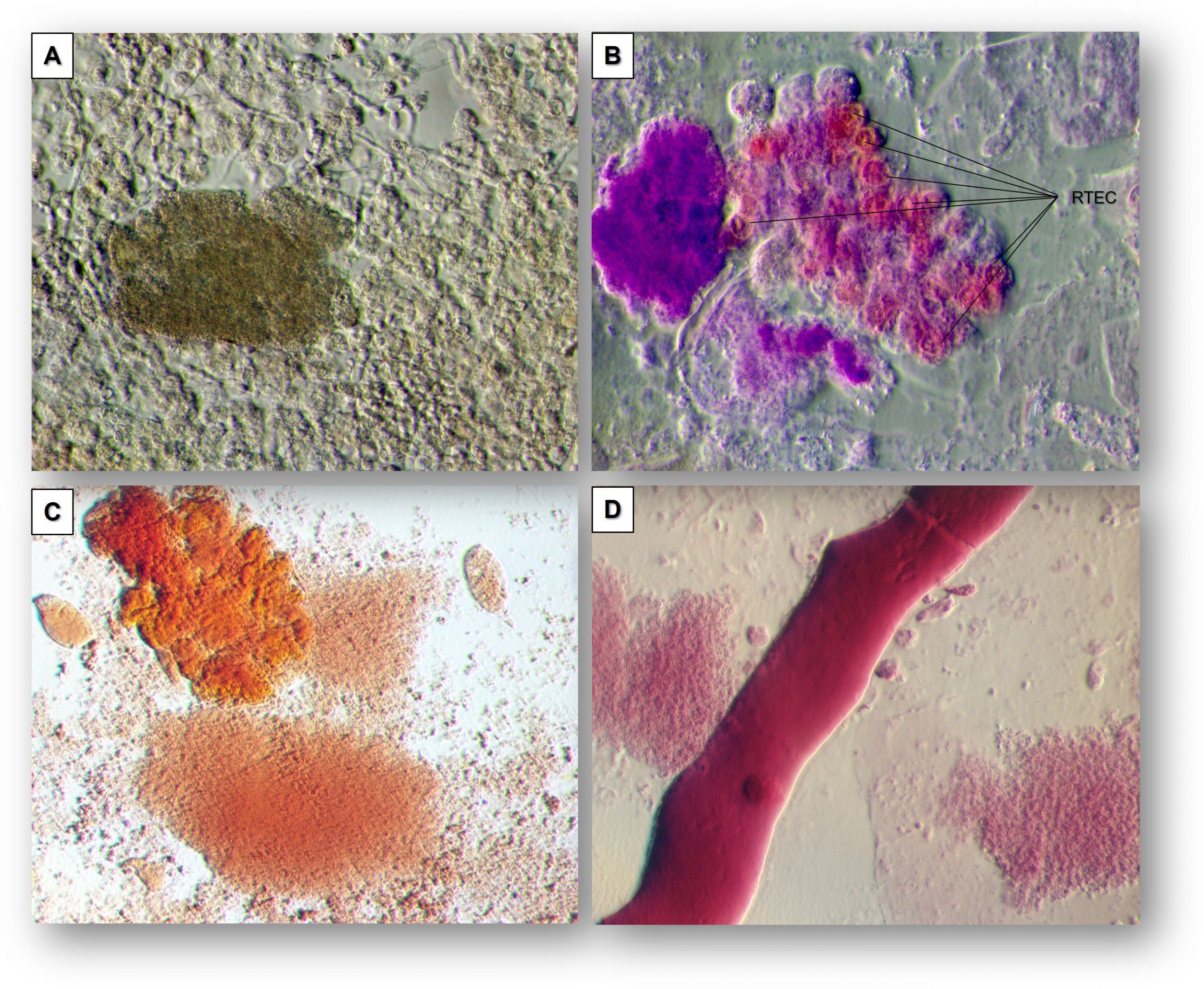

Oblique illumination can be particularly helpful to visualize a cast matrix that may not be very visible on bright or dark field illumination, particularly when phase contrast microscopy is not available (Figures 2-4).

It also allows for crisp visualization of cell nuclei and thus better characterization of the type of cells or cells free-floating in the urine sediment or embedded within casts.

The characteristic dysmorphism of acanthocytes is also nicely revealed by oblique illumination (Figure 5).

Post by Juan Carlos Velez

Edited by Anna Gaddy