IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common form of glomerulonephritis worldwide, and is responsible for ~10% of glomerulonephritis in the United States. IgA nephropathy can be primary or secondary. The pathophysiology of primary IgAN is complex and incompletely understood, but key events include abnormal glycosylation of IgA molecules and subsequent autoantibody development. An additional trigger such as infection may also be required. Secondary IgAN is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis (hepatic glomerulosclerosis), infection, and neoplasia. Additionally, IgA vasculitis (IgAV, formerly Henoch-Schonlein purpura) is a systemic form of IgAN.

IgAN most commonly affects males of Southeast Asian descent in the second or third decades of life, and often presents with episodic macroscopic hematuria and mild proteinuria in the setting of tonsillitis or pharyngitis. Approximately 25% of patients present with nephrotic syndrome and/or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Due to the frequently mild symptoms, the more indolent forms can remain undetected for years. Potential secondary causes should be excluded clinically. IgAV occurs primarily in children, and presents with some combination of purpuric rashes, gastrointestinal pain, arthritis, and hematuria/proteinuria.

The diagnosis of IgAN and reporting of relevant pathologic features in the renal biopsy report is made by synthesizing the immunofluorescence, light, and electron microscopic findings:

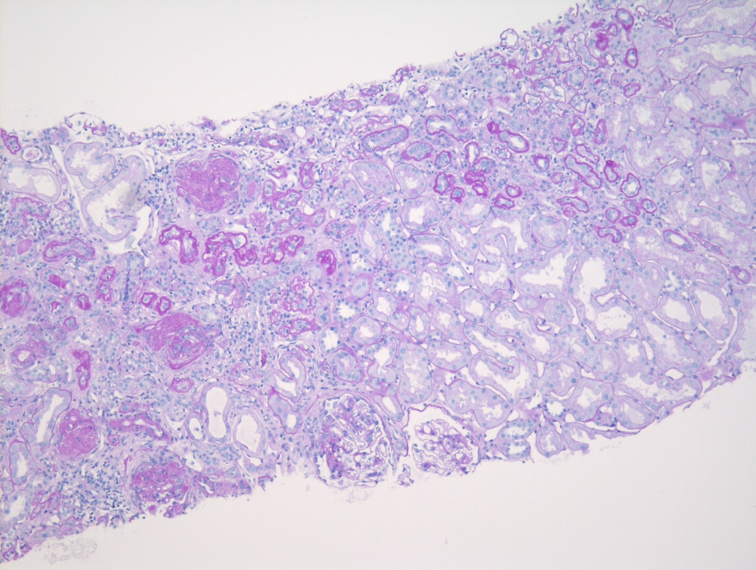

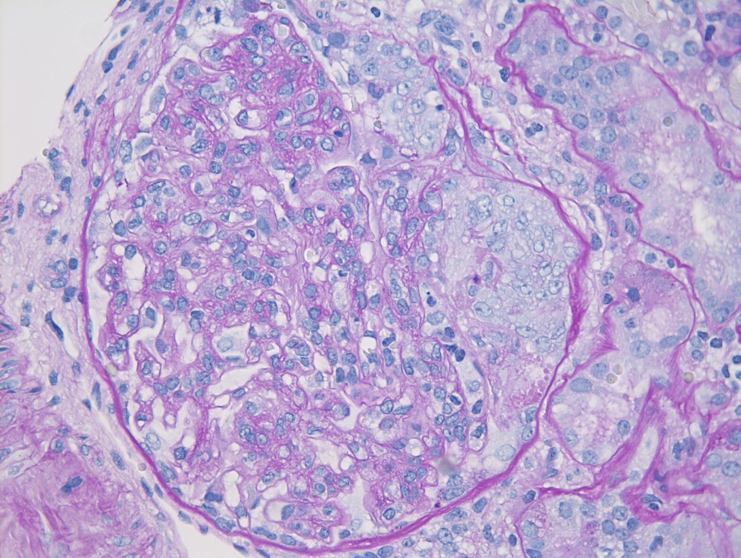

Light microscopy

Although the diagnosis of IgAN relies primarily upon immunofluorescence microscopy, light microscopy still plays an important role in the evaluation of IgAN. The variable clinical presentation and behavior of IgAN is a reflection of the underlying heterogeneity in light microscopic findings, ranging from essentially normal-appearing glomeruli to crescentic injury. The prototypical IgAN shows mesangial hypercellularity with increased mesangial matrix. Without immunofluorescence or electron microscopic studies, these prototypical histologic features can resemble the glomerular features of diabetic nephropathy, although the presence of intratubular red blood cells or red blood cell casts and the absence of glomerular and tubular basement membrane thickening may suggest nephritis.

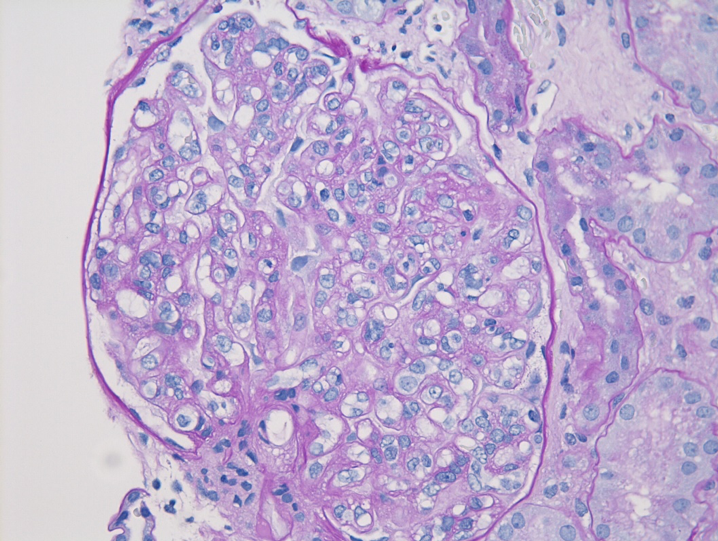

Given the variability of light microscopic features in IgAN, multiple classification schemes for IgAN have been developed. The best studied and most commonly used is the modified version of the Oxford Classification, which defines the “MEST-C” score through the evaluation of five pathologic variables: 1) mesangial hypercellularity (M); 2) endocapillary hypercellularity (E); 3) segmental glomerular sclerosis (S); 4) tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (T); and 5) cellular crescentic injury (C). The presence of endocapillary hypercellularity and cellular crescents identifies group of patients who could benefit from immunosuppressive therapy and may progress without it. The combination of mesangial hypercellularity and segmental sclerosis portends a deterioration of renal function, which is heightened by the additional presence of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Tubulointerstitial scarring is usually accompanied by progressive global glomerular sclerosis, which can eventually result in the development of an end-stage kidney.

Table 1: Oxford Classification of IgA Nephropathy

| Pathologic Variable | Definition | MEST-C Score |

| Mesangial hypercellularity | >4 mesangial cells in a mesangial area | M0: <50% glomeruli involved M1: >50% glomeruli involved |

| Endocapillary hypercellularity (ECH) | Increased cellularity within glomerular capillaries | E0: No EHC E1: Any ECH |

| Segmental glomerular sclerosis | Sclerosis in part of glomerulus | S0: No segmental sclerosis S1: Any segmental sclerosis |

| Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (IFTA) | % of renal cortex with IFTA | T0: 0-25% IFTA T1: 26-50% IFTA T2: >50% IFTA |

| Cellular crescents (CCs) | Proliferation of epithelial and inflammatory cells and fibrin in Bowman’s space, representing severe glomerular injury | C0: No CCs C1: 1-25% CCs C2: >25% CCs |

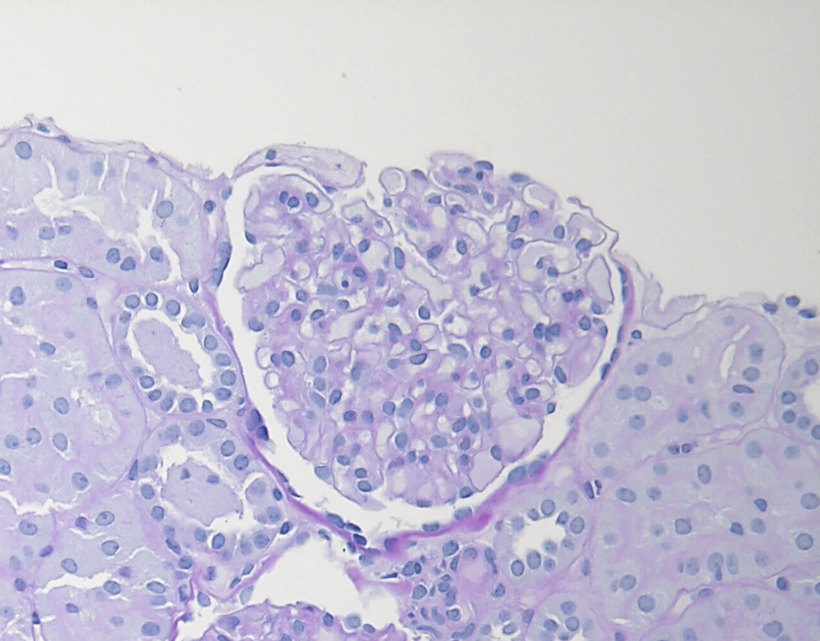

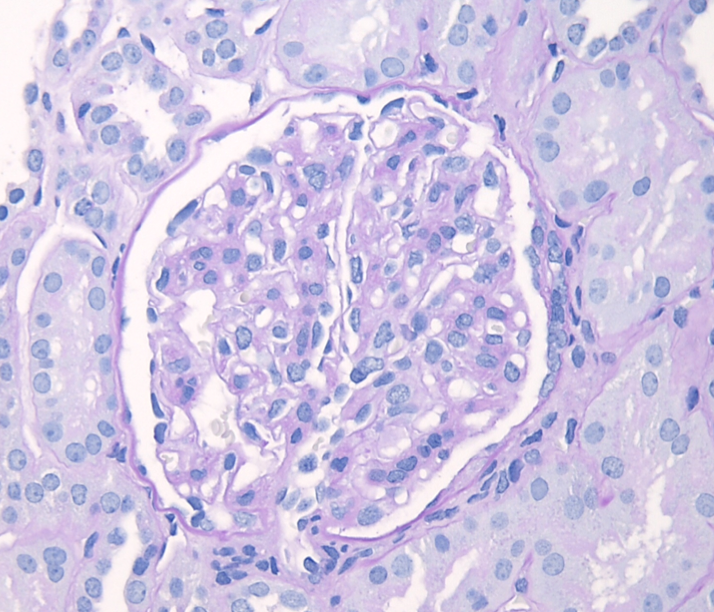

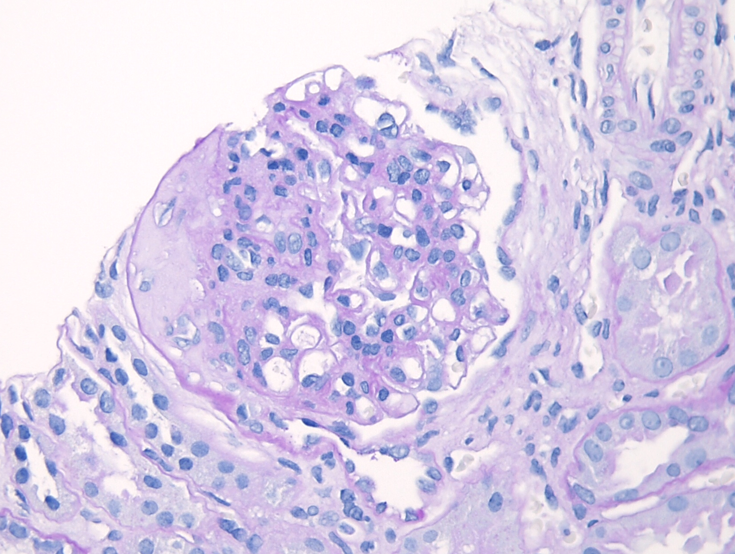

Figure 2: IgAN with M1 lesion, PAS stain. This glomerulus demonstrates mesangial hypercellularity with increased numbers of nuclei in the mesangial areas and increased mesangial matrix.

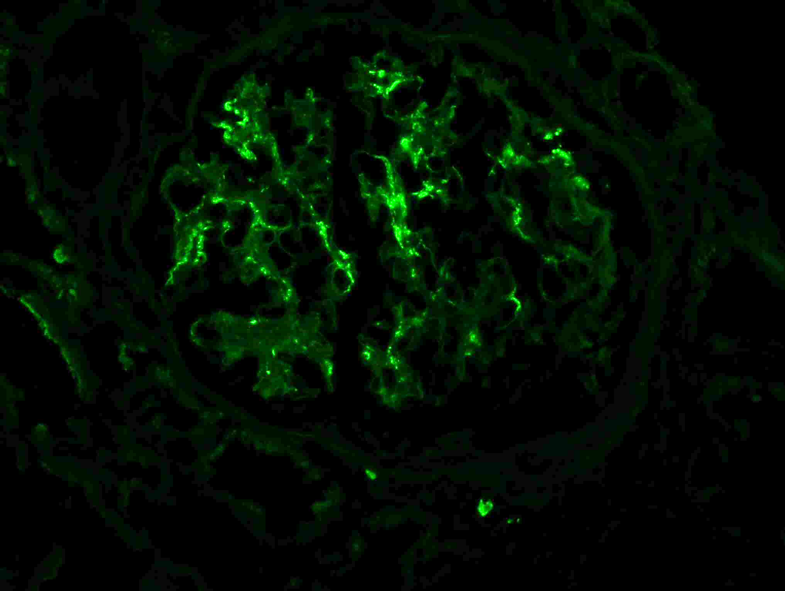

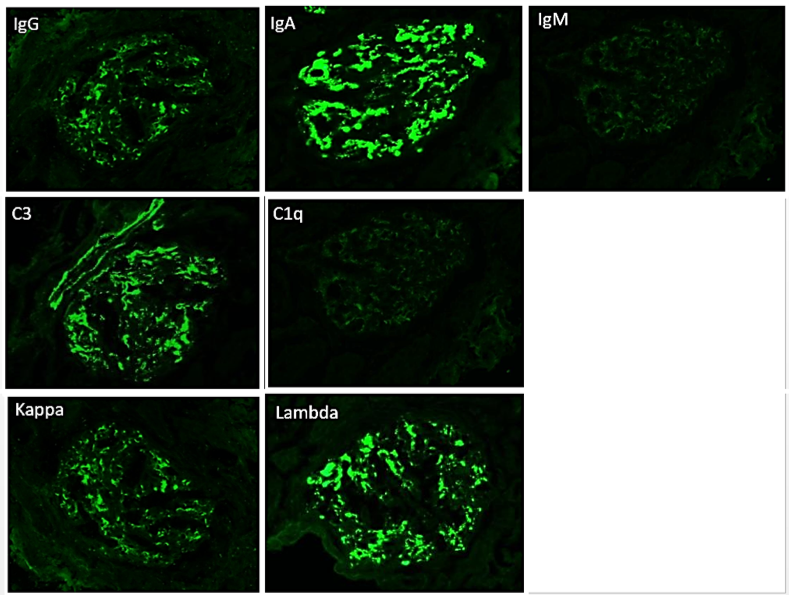

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The most critical feature in the diagnosis of IgAN is the finding of dominant or co-dominant IgA deposition in the glomeruli by immunofluorescence microscopy. Granular immunoglobulin deposition should be localized to the mesangium, and the presence of concomitant granular capillary wall staining often correlates with proliferative features (endocapillary hypercellularity) by light microscopy. Complement C3 is commonly co-deposited in the glomeruli. The presence of C1q deposition raises the possibility of secondary forms of IgAN such as hepatic glomerulosclerosis. Light chain staining is usually polyclonal, but lambda tends to be stronger than kappa. Mesangial fibrinogen staining is often present due to the propensity for fibrinogen to bind IgA molecules, but the presence of extracapillary fibrinogen staining suggests the presence of crescentic injury.

Figure 7: IgA deposition in IgAN. Immunofluorescence staining for IgA shows staining primarily in the mesangium, with only rare capillary wall staining.

Electron microscopy

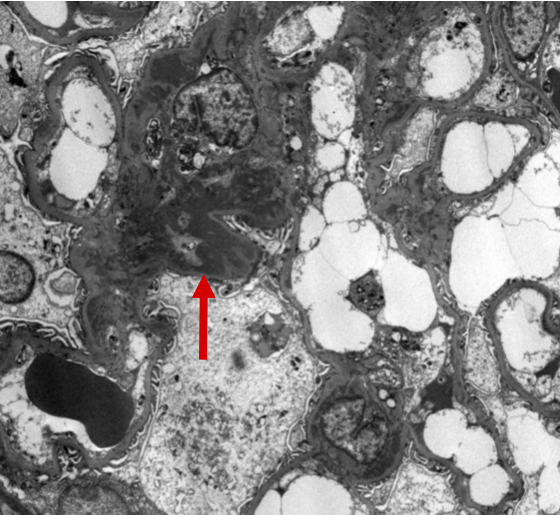

The electron microscopic findings in IgAN correlate with the immune complex deposition detected by immunofluorescence microscopy. The predominant finding is the presence of immune-type electron dense deposits in the glomerular mesangium. The deposits can be well-defined and easily discernible or vaguely-define and inconspicuous. Small scattered subendothelial deposits can be seen, but identification of large subendothelial deposits and multilayering of the glomerular basement membranes correlates with capillary wall staining by immunofluorescence microscopy and proliferative features (endocapillary hypercellularity) by light microscopy. Sparse subepithelial deposits may occasionally be seen, but the presence of numerous subepithelial “humps” in the setting of dominant or codominant IgA deposition suggests IgA-dominant Staphylococcal Infection-related Glomerulonephritis (IRGN).

Figure 9: IgAN electron microscopy with mesangial deposits. Ultrastructural examination of this glomerulus demonstrates localization of the immune-type electron dense deposits to the mesangial regions. The deposits appear as amorphous dense, dark areas (arrow).

Figure 10: IgAN electron microscopy with subendothelial deposits. Ultrastructural examination of this glomerulus demonstrates a subepithelial immune-type electron dense deposit between the glomerular basement membrane and the capillary lumen (arrow) as well as additional mesangial deposits (circle).

From the clinical perspective, the differential diagnosis of IgAN includes essentially any cause of hematuria, including various types of glomerulonephritis and basement membrane abnormalities such as Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy. The major pathologic differential diagnosis for IgAN are IgAV and IgA-dominant Staphylococcal IRGN. The diagnosis of IgAV cannot be reliably differentiated from IgAN on biopsy alone, as it is considered to be a systemic counterpart to IgAN and the histology is identical. Correlation with patient age and clinical findings is necessary. IgA-dominant Staphylococcal IRGN typically occurs in middle-aged or elderly diabetic patients with active Staphylococcus infections and hypocomplementemia.

Although the light microscopic patterns can overlap, IgA-dominant Staphylococcal IRGN is more likely to show endocapillary hypercellularity and intracapillary neutrophils than IgAN. Histologic features of diabetic nephropathy are often present. Immunofluorescence microscopy shows mesangial and capillary wall IgA staining which is typically dominant or co-dominant, but C3 can occasionally be stronger than IgA. Electron microscopy is particularly helpful and shows large subepithelial “humps” in addition to mesangial deposits. It should also be noted that because IgAN is so common and often mild, the finding of IgAN by biopsy may not be the only diagnosis, and may not be the explanation for the patient’s clinical symptoms, such as IgAN with superimposed pauci-immune glomerulonephritis.

Alexander Gallan, MD

Assistant Professor of Pathology, The Medical College of Wisconsin

INTERESTING