The zebrafish kidney is being increasingly studied, as it appears to offer several advantages for studying renal function. For one, it is transparent, allowing one to visualize kidney development in real-time. Second, it is a simplified system consisting of a single glomerulus with two tubules which nonetheless appear to have proximal and distal segments similar to the mammalian kidney. Its large number of offspring produced make it ideal for genetics as well. Finally, it has also been successfully shown to be a model for various disease states, such as polycystic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, and aminoglycoside-induced renal failure.

The zebrafish kidney is being increasingly studied, as it appears to offer several advantages for studying renal function. For one, it is transparent, allowing one to visualize kidney development in real-time. Second, it is a simplified system consisting of a single glomerulus with two tubules which nonetheless appear to have proximal and distal segments similar to the mammalian kidney. Its large number of offspring produced make it ideal for genetics as well. Finally, it has also been successfully shown to be a model for various disease states, such as polycystic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, and aminoglycoside-induced renal failure.

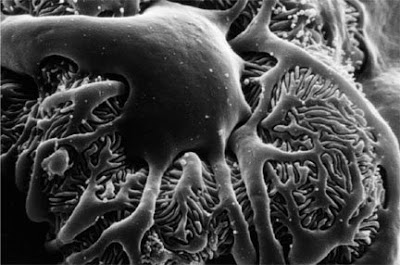

Over the past few days at the MDIBL “Origins of Renal Physiology” course, we have been conducting experiments with zebrafish glomerular filtration. To begin with, we exposed fish to puromycin, a drug known to directly cause podocyte injury (zebrafish are already known to have podocytes). Then, fish were injected with a fluorescently-labeled dextran with a molecular weight of 70kD. Over the next several days, we looked at the rate of disappearance of immunofluorescence, a marker for dextran clearance. Fish untreated with puromycin showed a relatively constant fluorescence–indicating that an intact filtration barrier does not allow 70kD molecules to pass through it. However, fish treated with puromycin showed a dramatic decrease in immunofluorescence–indicating that the podocyte damage induced by puromycin allowed the 70kD dextran to pass through the filtration barrier.