Cystinosis is an autosomal recessive disease caused by a mutation in CTNS, which encodes the lysosomal transporter of cystine. Without this, cystine gradually accumulates in cells causing progressive damage. The commonest kind is “nephropathic cystinosis” which is the juvenile form and presents in infancy although there are milder adolescent and adult forms. It is a rare disease with only 6,000 sufferers worldwide.

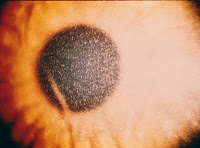

It is characterized by the early development of fanconi syndrome with progressive loss of tubular function leading to ESRD by the age of 10. Most affected children are blond and have marked growth retardation. Corneal deposits are common and can cause blindness later in life. Patients may also have hepatosplenomegaly, muscle weakness, delayed puberty and eventual neurological disease. The adult form is more benign and usually presents with visual problems although it can lead to ESRD in some patients.

There is an effective treatment for cystinosis – cysteamine, given orally, enters the lysosomes and reacts with cystine forming a complex that can exit the lysosome and prevent build-up. It should be started as soon as the disease is diagnosed but even with this, the tubular defects often persist. However, there is a definite improvement in overall renal prognosis with this drug. So, if there is an effective treatment, why do many children with this disease still go on to require renal transplantation? There are huge issues surrounding compliance with the medication. It needs to be taken four times daily at equal intervals. More importantly, it causes severe halitosis and body odor that, for a young child, can be devastating. I had a patient a number of years ago who told me that he and his brother had to be removed from class because the problems with bad odors while on the drug and that he preferred going on dialysis and getting a transplant than remaining on the treatment. Unfortunately, at that time, he was developing severe visual problems related to build-up of cystine in his corneas.

There may be some more light at the end of the tunnel. Recently, phase III trials were completed on a new formulation of cysteamine. This can be given twice daily, has a lower total cumulative dose than the standard formulation and appears to cause less halitosis and body odor. According to the company, 40 of 41 patients enrolled in the study decided to continue the drug after the phase III period had ended. This is certainly encouraging.

As Nate mentioned previously, this should not be confused with cystinuria, a disease of amino acid transport in the kidney leading to an increased susceptibility to kidney stones.