Our focus on myeloma related disorders continues- view previous posts here.

Glomerular diseases with organized deposits belong to a broad group of paraprotein-related diseases that affect the kidneys. The presence of substructure or organization to deposits is often a clue to an underlying lymphoproliferative or myelomatous process; and is therefore a key ultrastructural finding to assess for when dealing with immune complex deposition.

Deposits may be seen in all compartments of the kidney (glomeruli, tubules, interstitium and blood vessels); leading to various clinical manifestations depending on which anatomic structure is being affected (i.e. hematuria, proteinuria, hypertension or renal impairment). Glomerular diseases with organized deposits may occur in non-MGRS kidney lesions as well, however any time organized deposits are encountered it is important to rule out underlying myeloma/lymphoproliferative disorder.

For an algorithmic approach to renal diseases with organized deposits, please refer to this link.

Classification of MGRS associated renal lesions

A consensus report from the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group categorizes MGRS-associated renal lesions as:

As part of the on-going RFN series, this post will review select MGRS-associated kidney lesions that present with organized deposits, highlighting the key pathology findings in: Immunoglobulin-related amyloidosis, Monoclonal fibrillary glomerulonephritis, Immunotactoid glomerulonephritis, and Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis.

1. Ig-related amyloidosis (AL/AH/AHL Amyloidosis)

Amyloidosis derived from light chains (AL), heavy chains (AH) or both (AHL). AL amyloid is the most common form of amyloid (followed by AA and ALECT2). AH and AHL are rare.

- Light microscopy

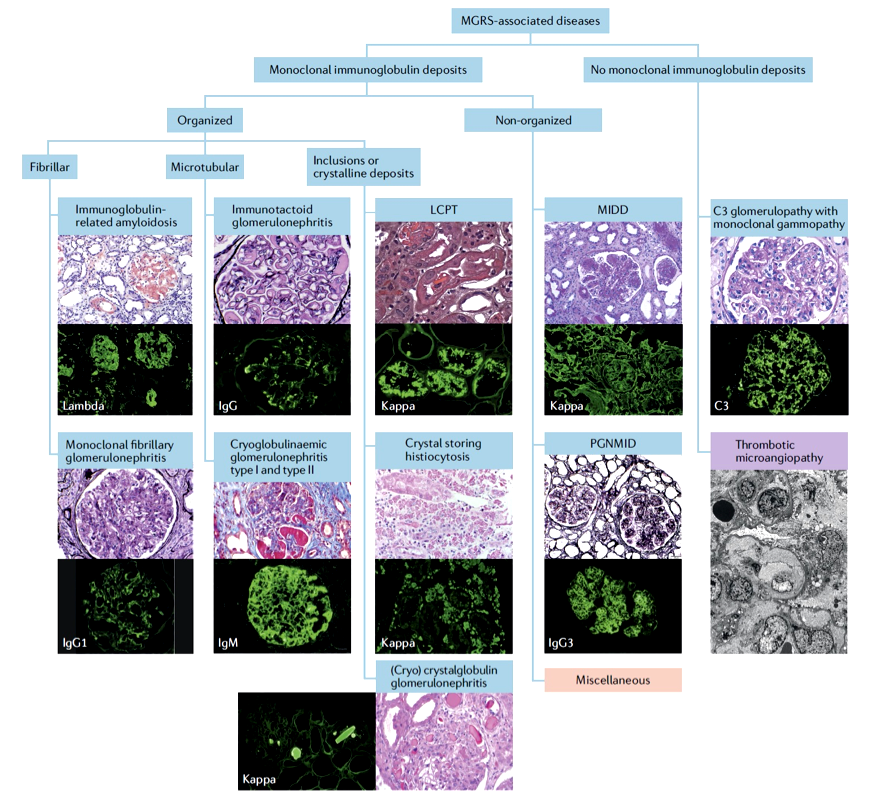

- Mesangial areas widened with amorphous pink material that is pale/negative on PAS. This separates it from other forms of mesangial matrix accumulation such as IgA nephropathy and diabetes (which would be PAS positive) [Image 1].

- Amorphous deposits in small vessels, which may mimic hyalinosis. Again trichrome and PAS stain are helpful in differentiation.

- Trichrome will stain will also help pickup interstitial amyloid deposits, which will stain a light blue grey color as opposed to interstitial fibrosis which will be bright blue (depending on your trichrome stain).

- Amyloid often affects the peripheral capillary loops of glomeruli and can form spikes which have a classic “cock’s comb” appearance. This is best appreciated on the Jones silver stain.

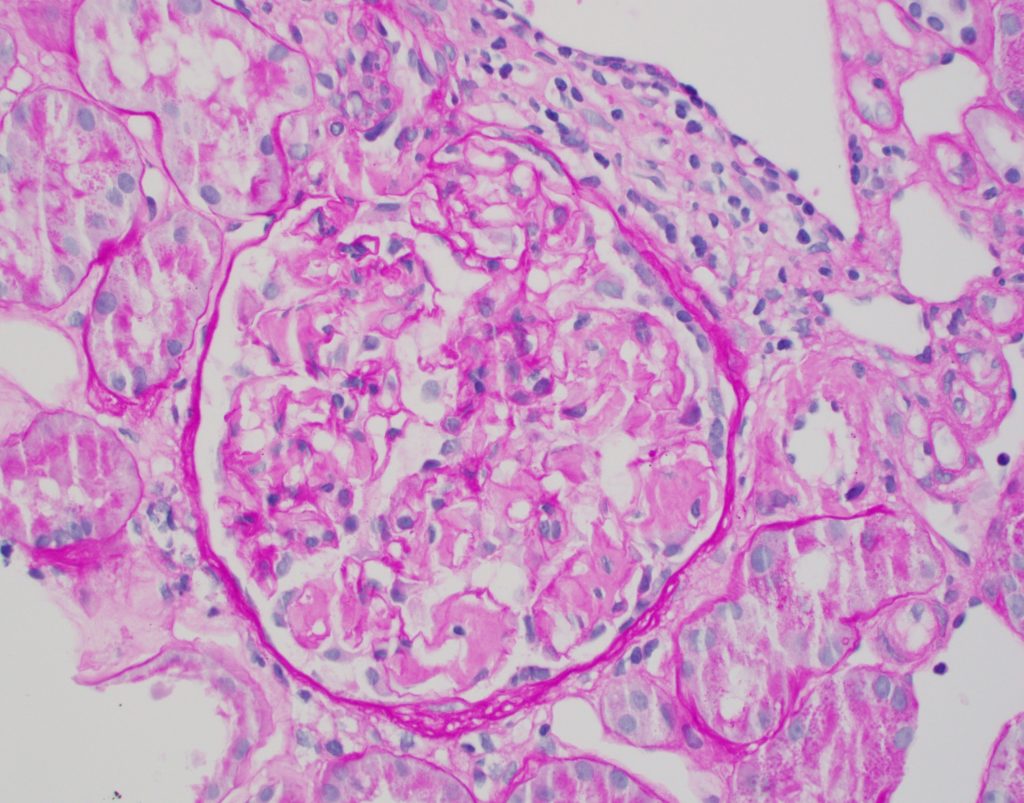

- Congo red staining is needed to confirm amyloid, and the deposits will show appropriate birefringent properties when viewed under polarized light [Image 2].

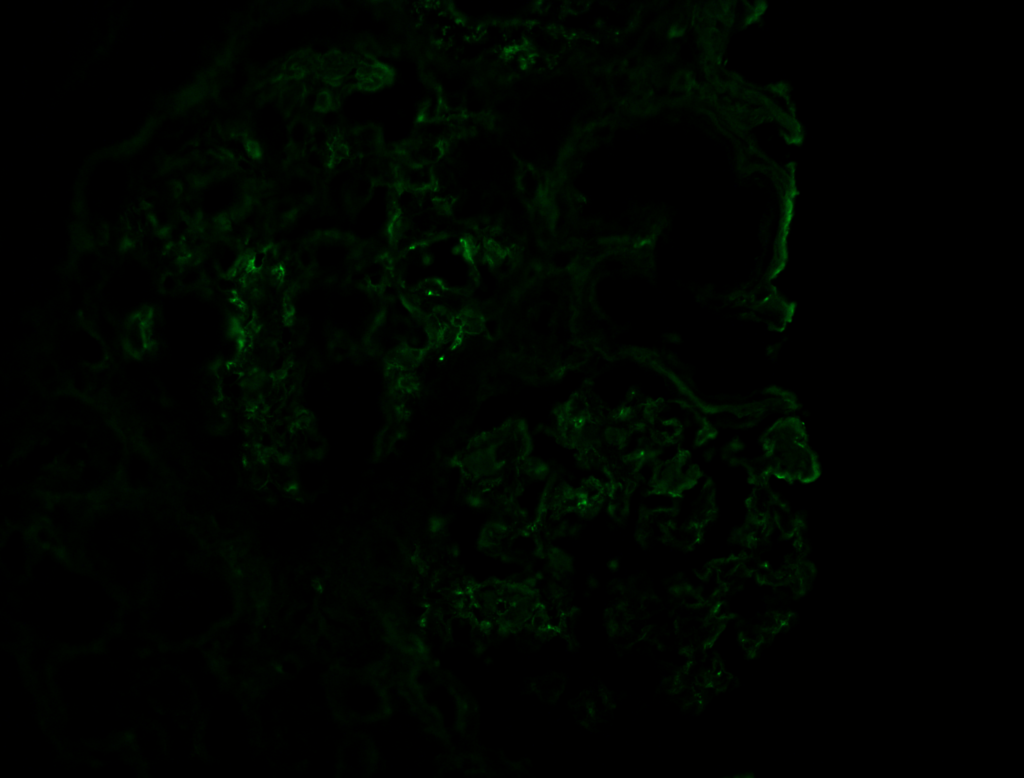

- Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF)

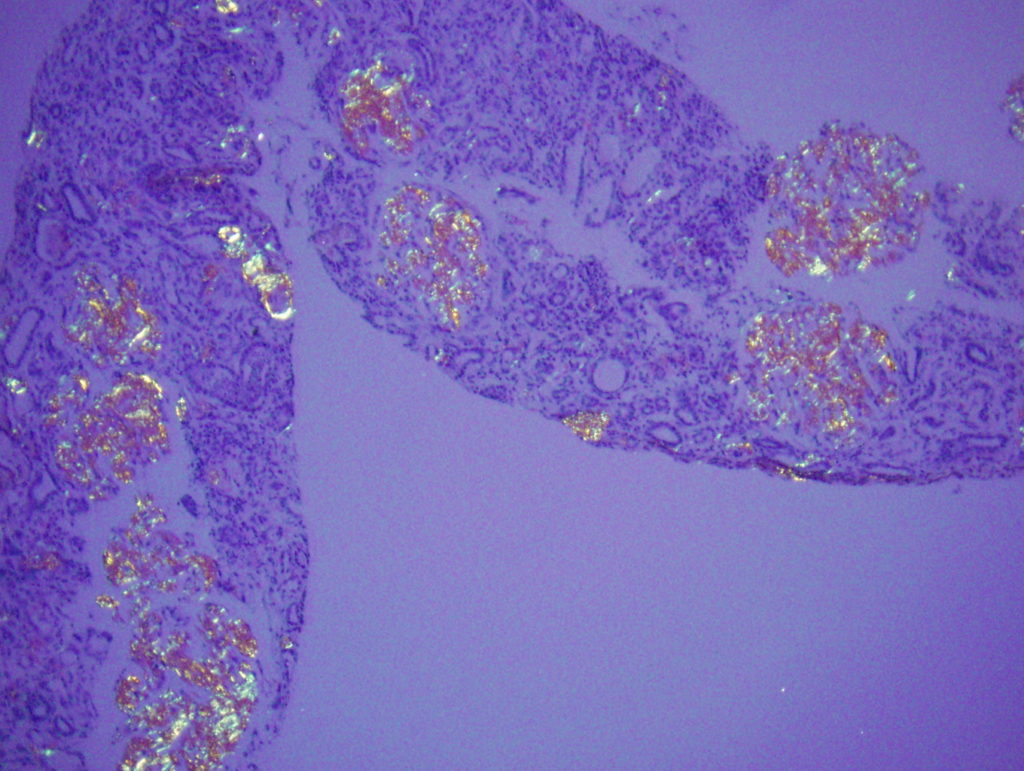

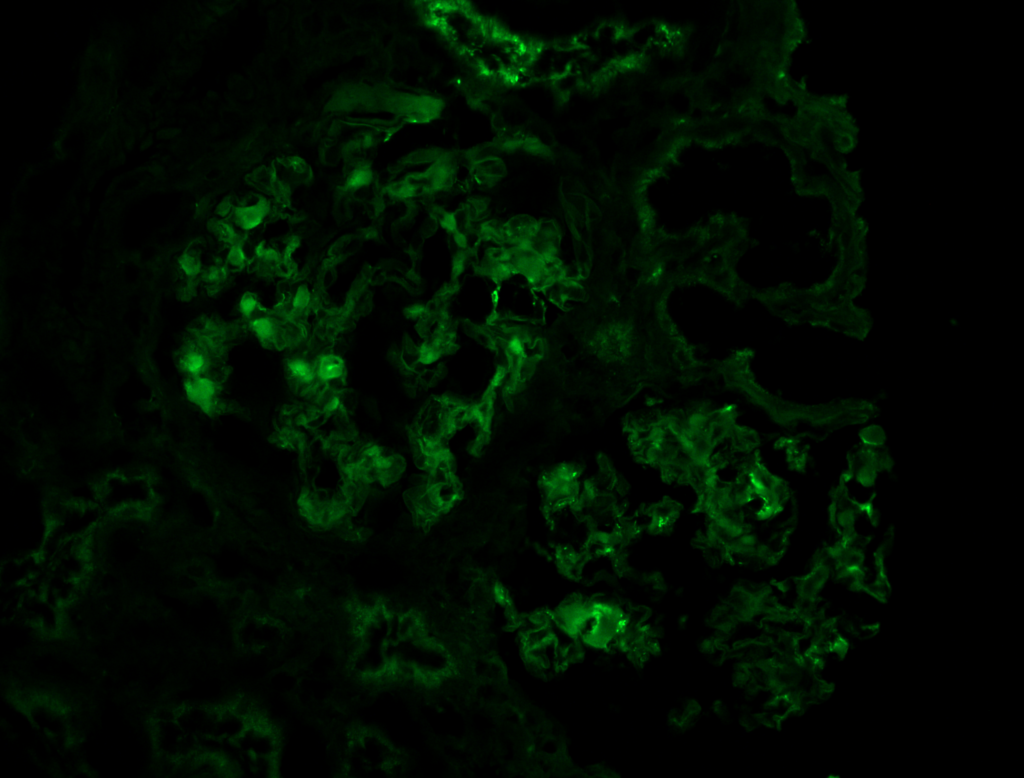

Corresponding heavy chains or light chains will show smudgy positivity, depending on type of amyloid [Image 3 & 4].

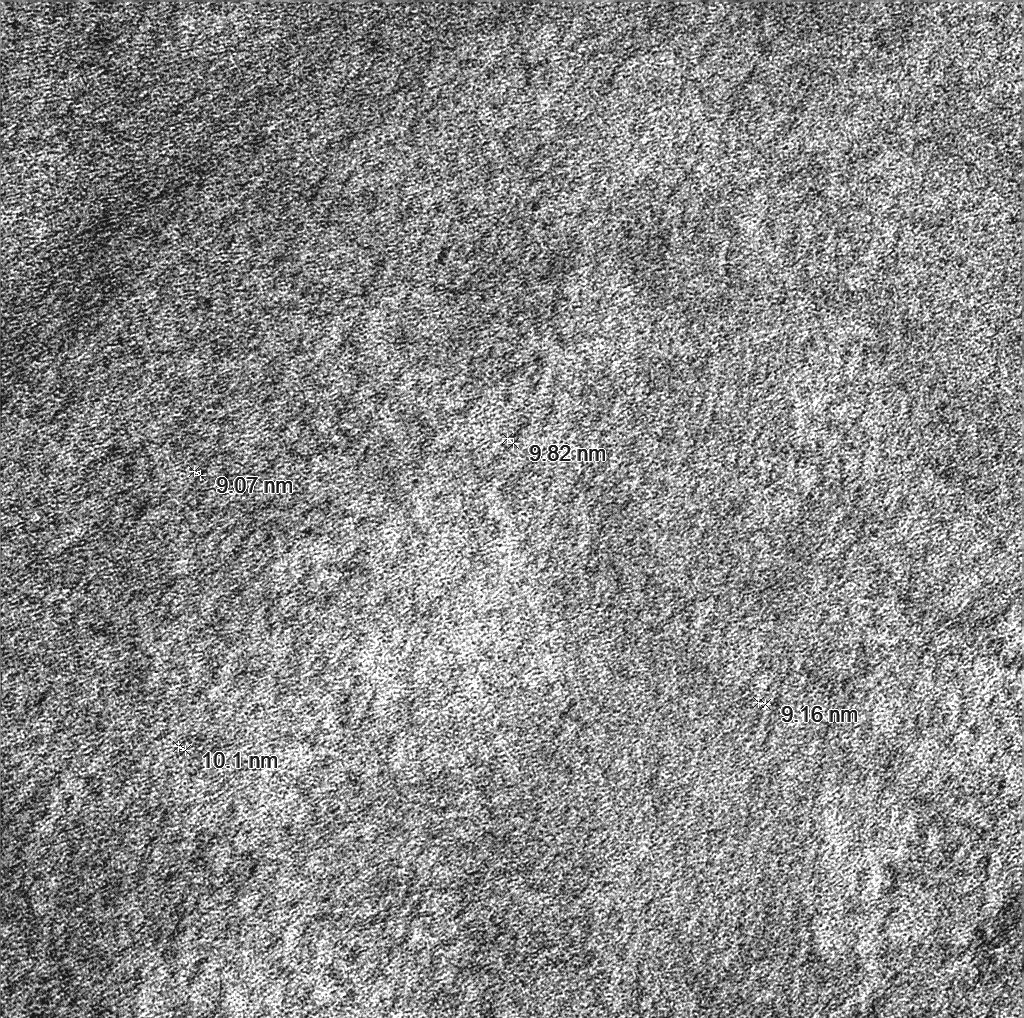

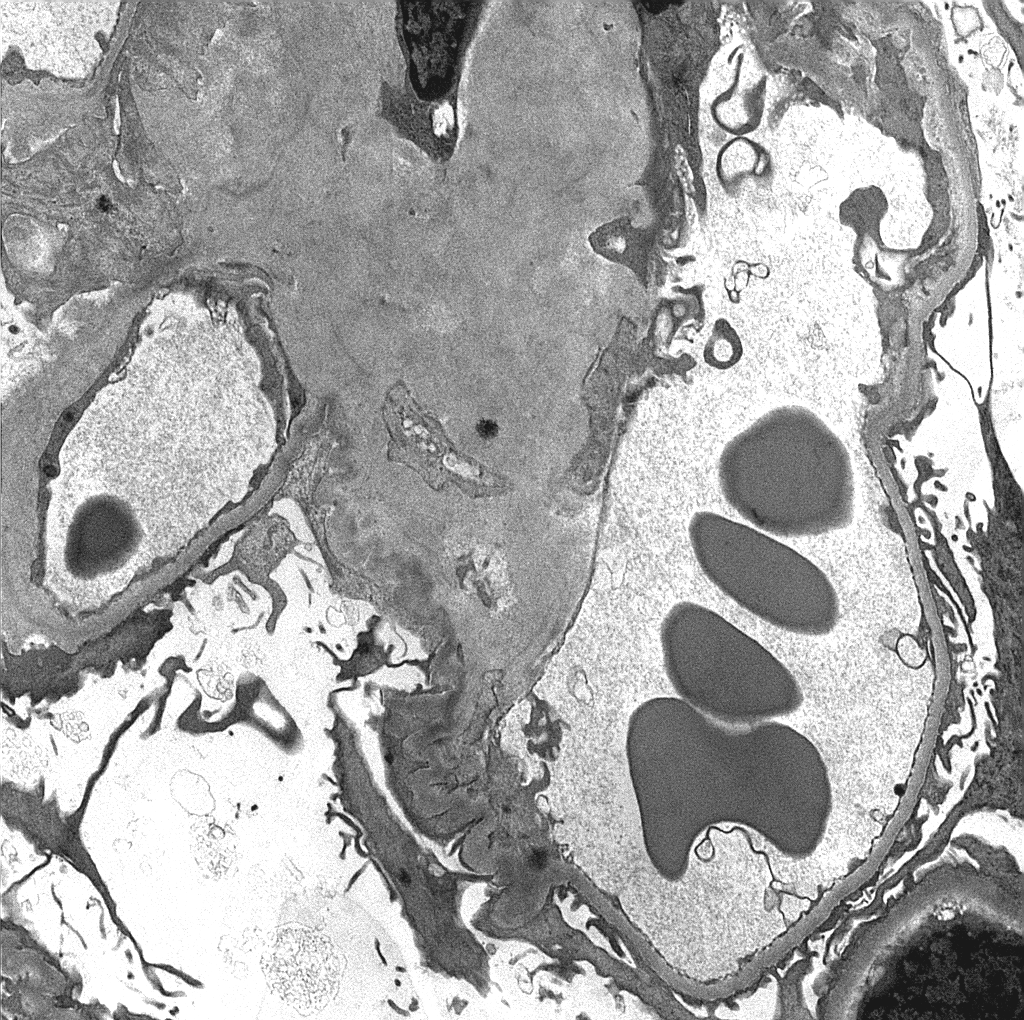

- Electron microscopy (EM)

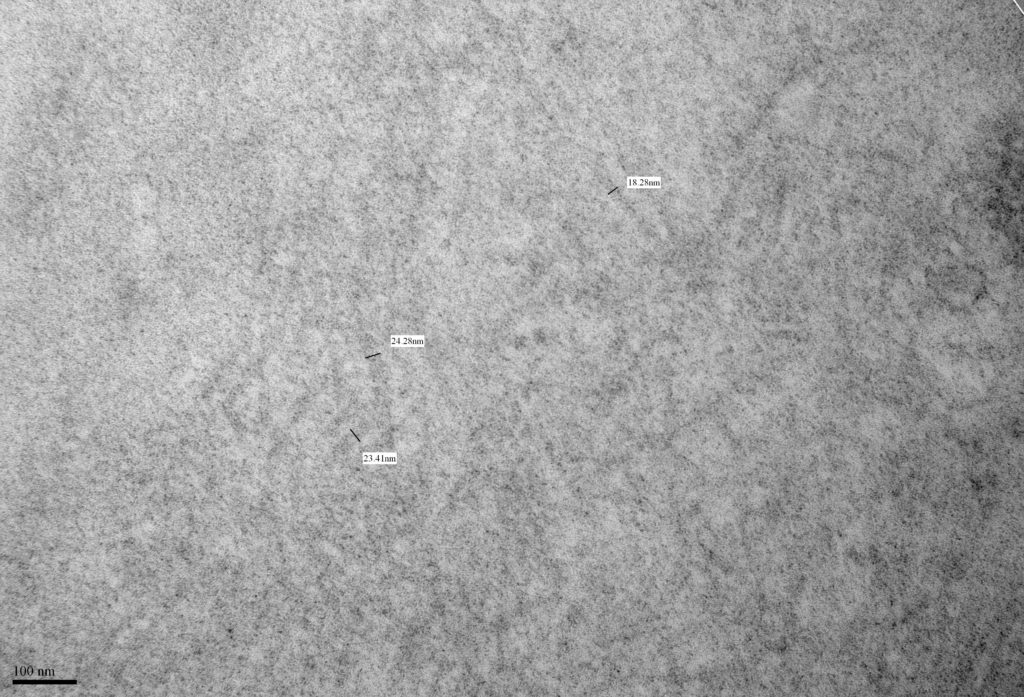

- Amyloid forms fibrils which are randomly (haphazardly) arranged and measure 8-12 nm in diameter [Image 5].

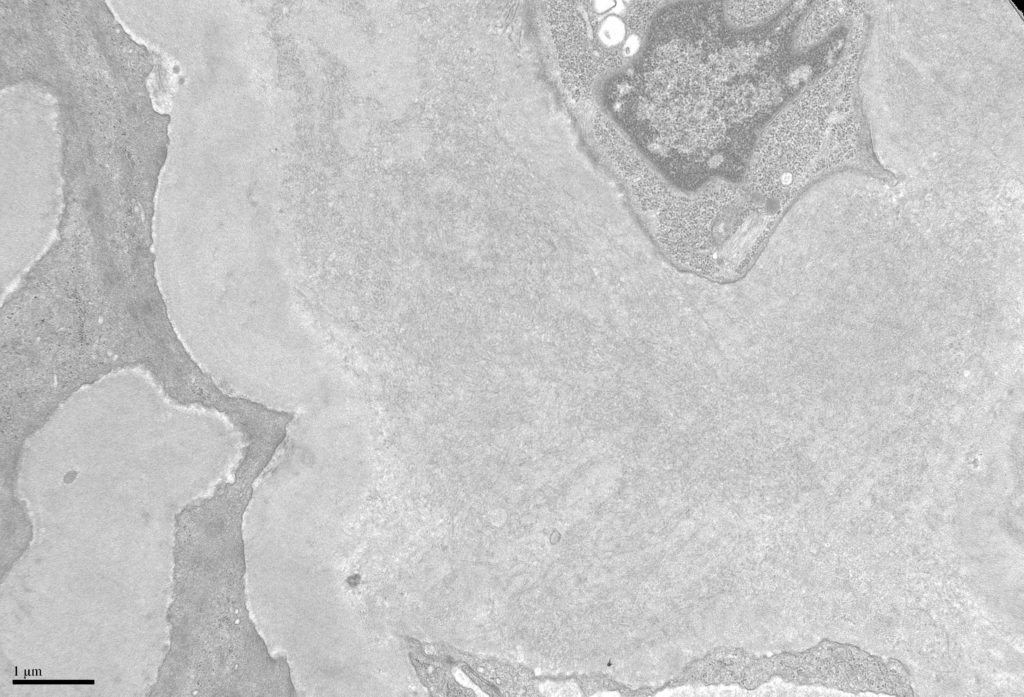

- Fibrils may be seen in all compartments of the kidney [Image 6].

- Amyloid often has an infiltrative appearance invading through basement membranes.

- Immune complexes may also be seen, which may necessitate a concurrent diagnosis of immunoglobulin deposition disease.

- Mass spectrometry

In some cases where immunofluorescence stains are unable to type the amyloid, mass spectrometry is required. Overall mass spectrometry is the gold standard for typing amyloidosis. However many laboratories use a cost effective approach with immunofluorescence stains as the first step, followed by mass spectrometry in select cases.

2. Monoclonal fibrillary glomerulonephritis

Fibrillary glomerulonephritis is a rare disease occurring in less than 1% of all native kidney biopsies.

Apart from myeloma/lymphoproliferative disorders non-monoclonal forms of fibrillary glomerulonephritis can be associated with other malignancies, autoimmune disease and chronic viral infections (especially chronic Hepatitis C).

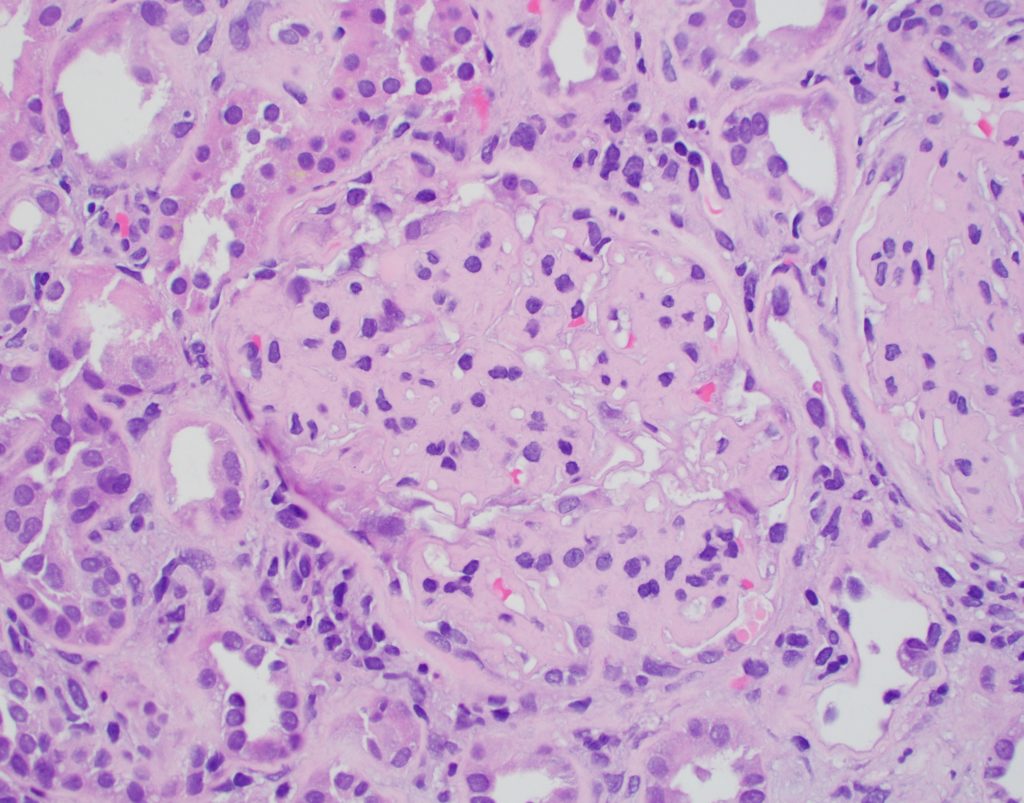

- Light microscopy:

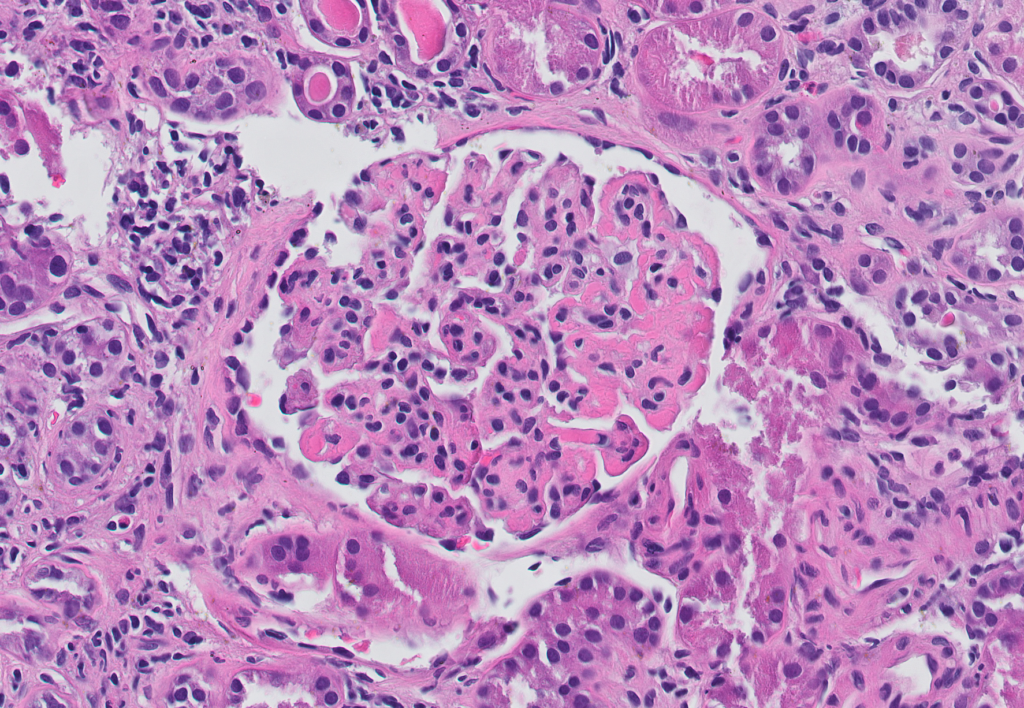

- Diffuse mesangial expansion. Peripheral capillary walls are often thickened [Image 7].

- Fibrillary glomerulonephritis can often show crescents, a feature unusual in amyloidosis.

- Congo red is classically negative, although exceptions to this rule do exist.

- DNAJB9 may be positive in non-monoclonal forms of fibrillary glomerulonephritis; however the monoclonal forms are often DNAJB9 negative.

- Immunofluorescence microscopy:

- In non-monoclonal forms of fibrillary glomerulonephritis, the staining is variable with positivity for various antibodies. In the monoclonal form there is restriction heavy and light chains.

- IF may be helpful to detect focal fibrillary deposits in other compartments of the kidney.

- Electron microscopy:

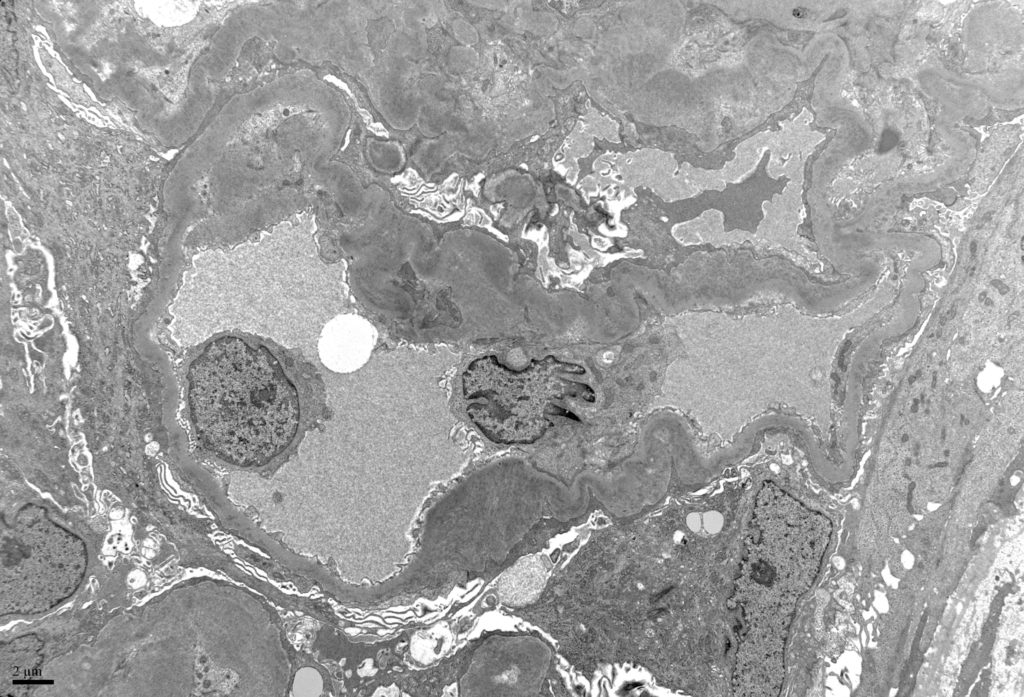

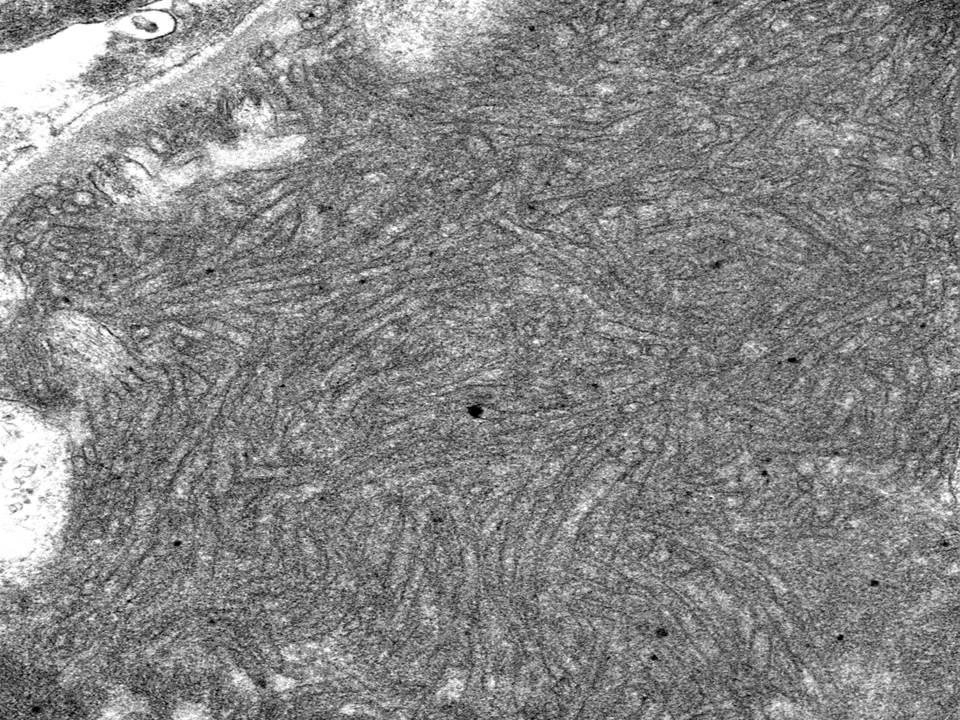

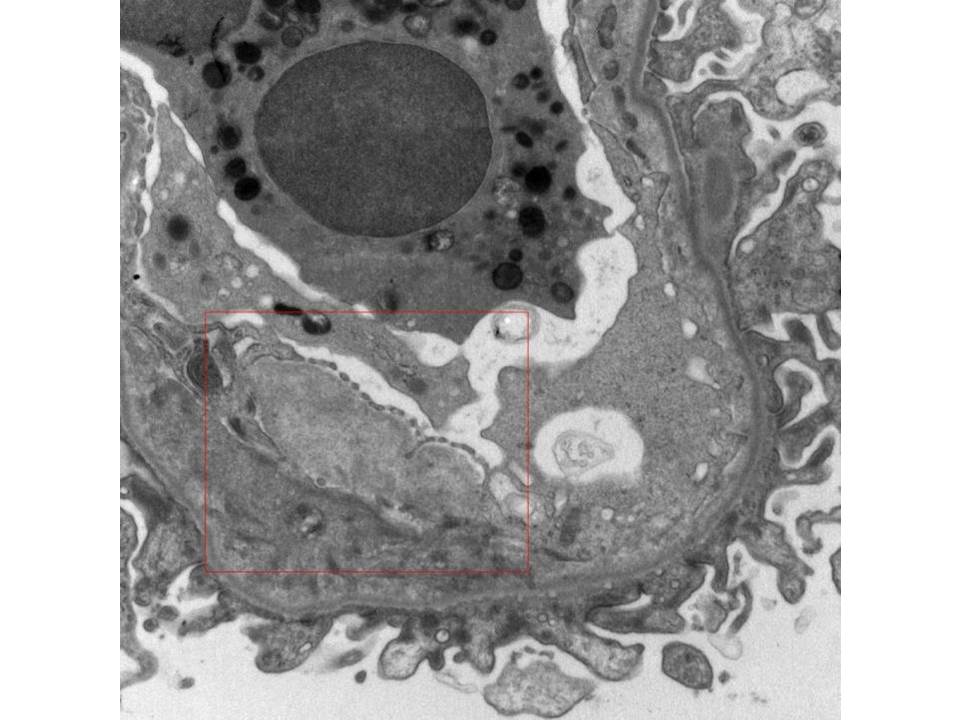

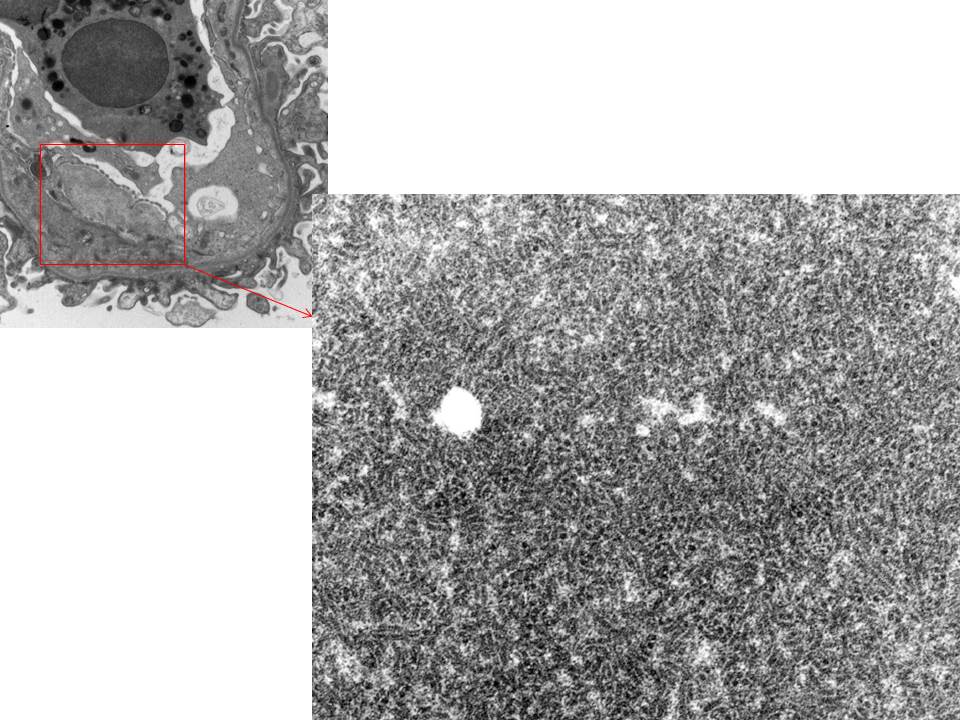

- Fibrillary glomerulonephritis shows randomly distributed fibrils measuring 10-30 nm in diameter [Image 8 & 9].

- Deposits are usually seen in mesangial areas and along peripheral capillary walls [Image 10].

- Deposits makes be seen in other compartments of the kidney. Tubular basement membrane immune complexes may be seen.

3. Immunotactoid glomerulopathy

Glomerulopathy characterized ultrastructurally by microtubular deposits with hollow cores typically >30 nm in diameter (usually 50-100 nm) [Image 11].

Light microscopic patterns are variable and include mesangioproliferative, membranoproliferative, membranous and endocapillary proliferative patterns.

Congo red stain is negative.

Immunofluorescence stains show heavy chain or light chain restriction.

4. Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis caused by monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition in the setting of cryoglobulinemia.

Clinically characterized by cutaneous symptoms, hypocomplementemia and renal dysfunction.

- Light microscopy:

- Classically a membranoproliferative pattern of injury

- Intracapillary thrombi composed of immune complexes (“hyaline thrombi”) [Image 12].

- Histologic changes may be subtle, and thus cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis is often diagnosed at the ultrastructural level only (in the correct clinical setting).

- Congo red stain is negative.

- Immunofluorescence microscopy

Granular staining with restriction for heavy and light chains

- Electron microscopy

- Intracapillary, subendothelial, mesangial deposits showing substructure [Image 13].

- Patterns of substructure include fibrils, lattice-type pattern, small tubules without hollow cores, or small aggregates of straight or curved bundles [Image 14].

- Deposits may be subtle, and in fact a diagnosis of cryoglobulinemia glomerulonephritis should be considered when immune complexes are scant/difficult to appreciate.

Camilo Cortesi, MD

Nephrology fellow, UCSF