In the routine urinary sediment examination, you may come across 4 types of nucleated cells:

1. Squamous epithelial cells

2. Leukocytes

3. Transitional epithelial cells

4. Tubular epithelial cells

Let’s discuss how to differentiate between them.

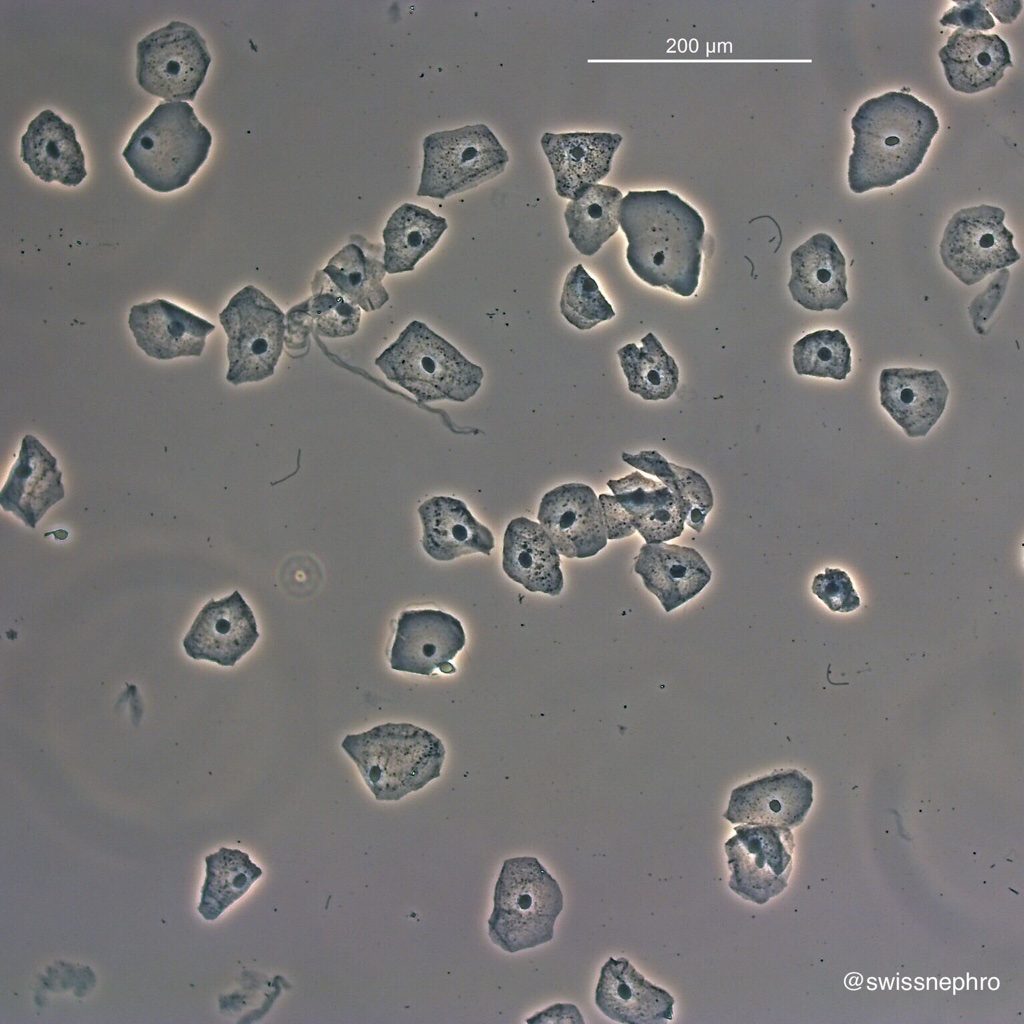

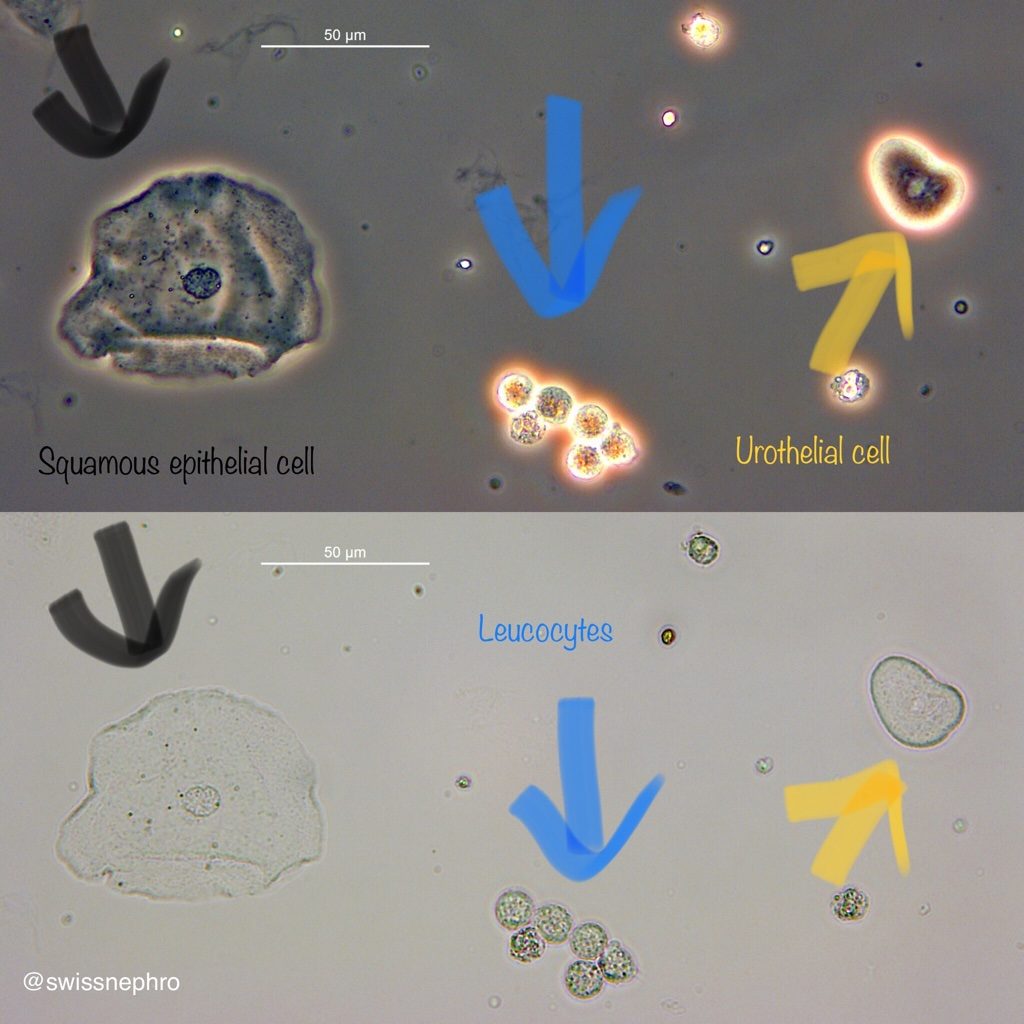

Squamous epithelial cells are easily identified by their huge size and polygonal shape (Fig. 1 and 2). They signify contamination of the urine with vaginal or urethral content.

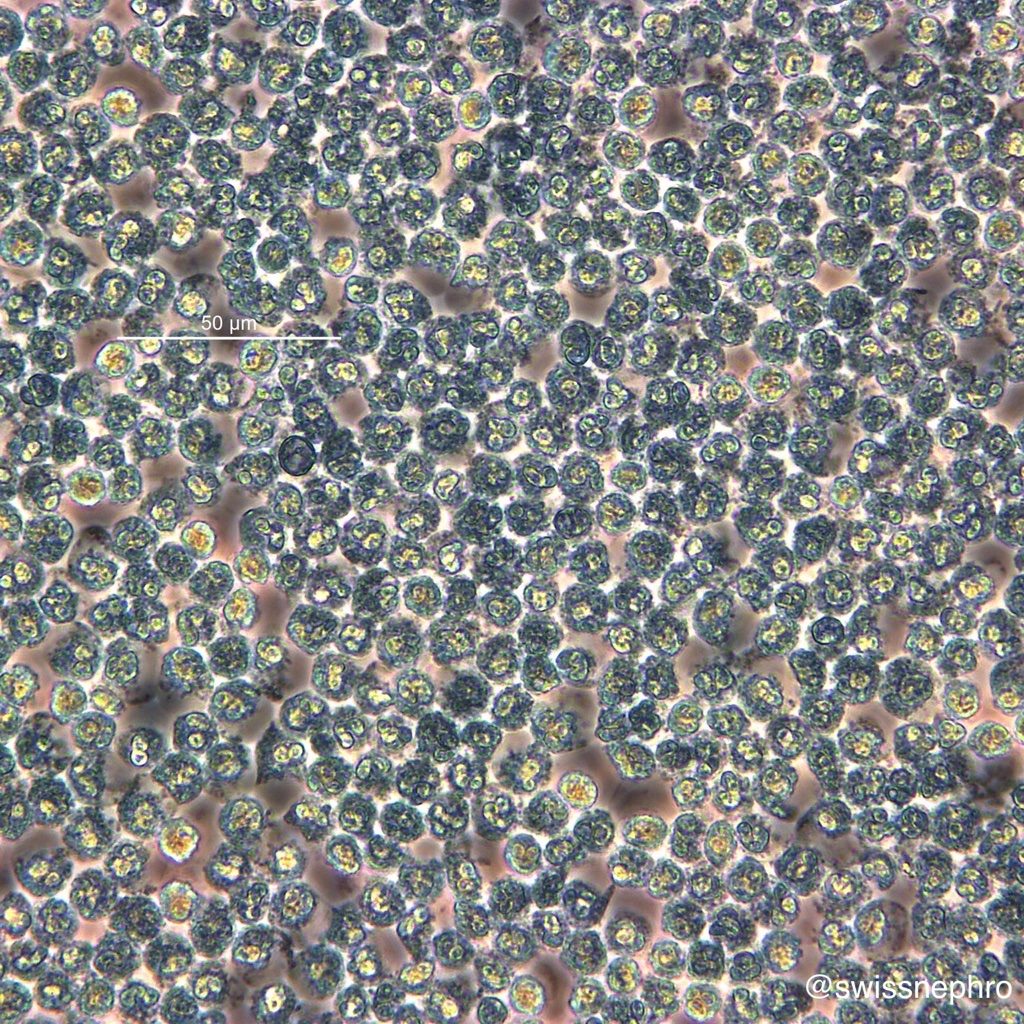

Leukocytes, a sign of kidney or urinary tract inflammation, are much smaller and show an overall granular texture (Fig. 3). Polymorphonuclear cells with typical lobulated nuclei are most common (Fig.4).

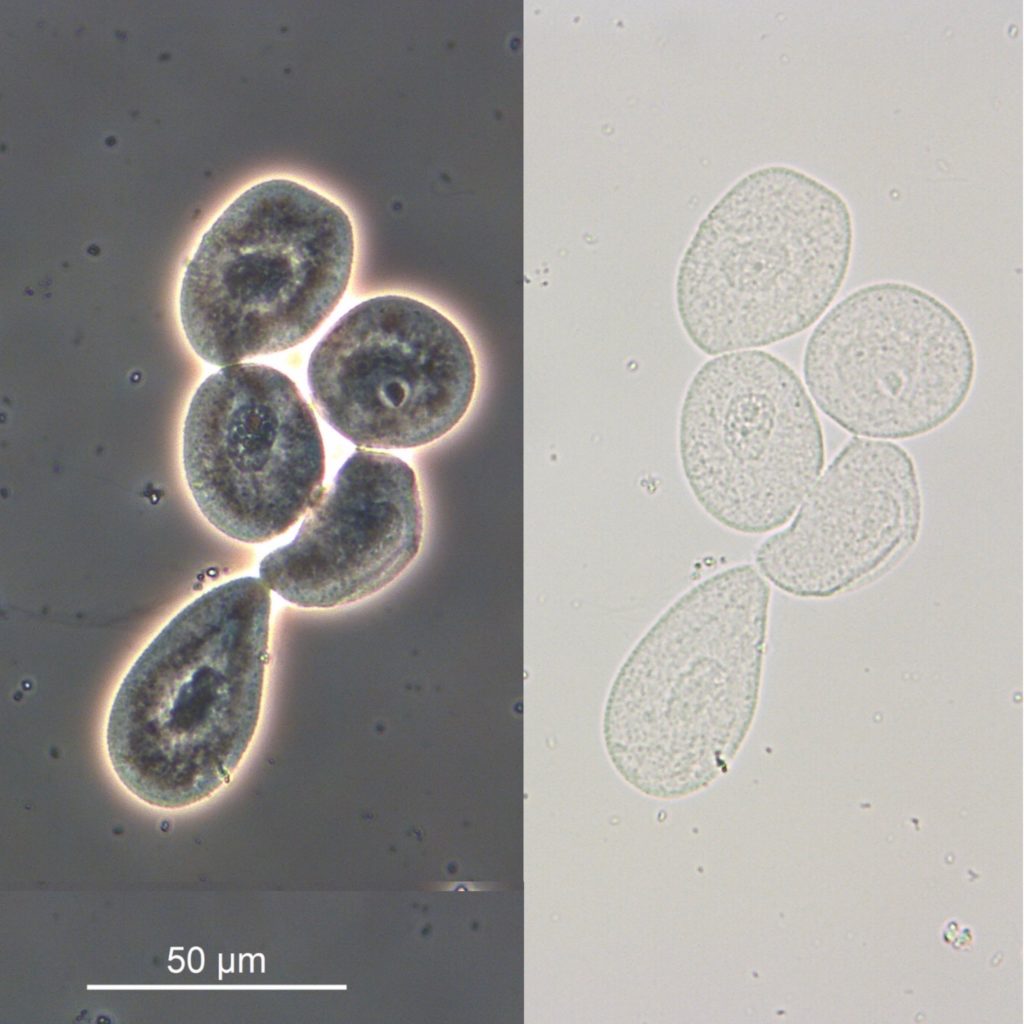

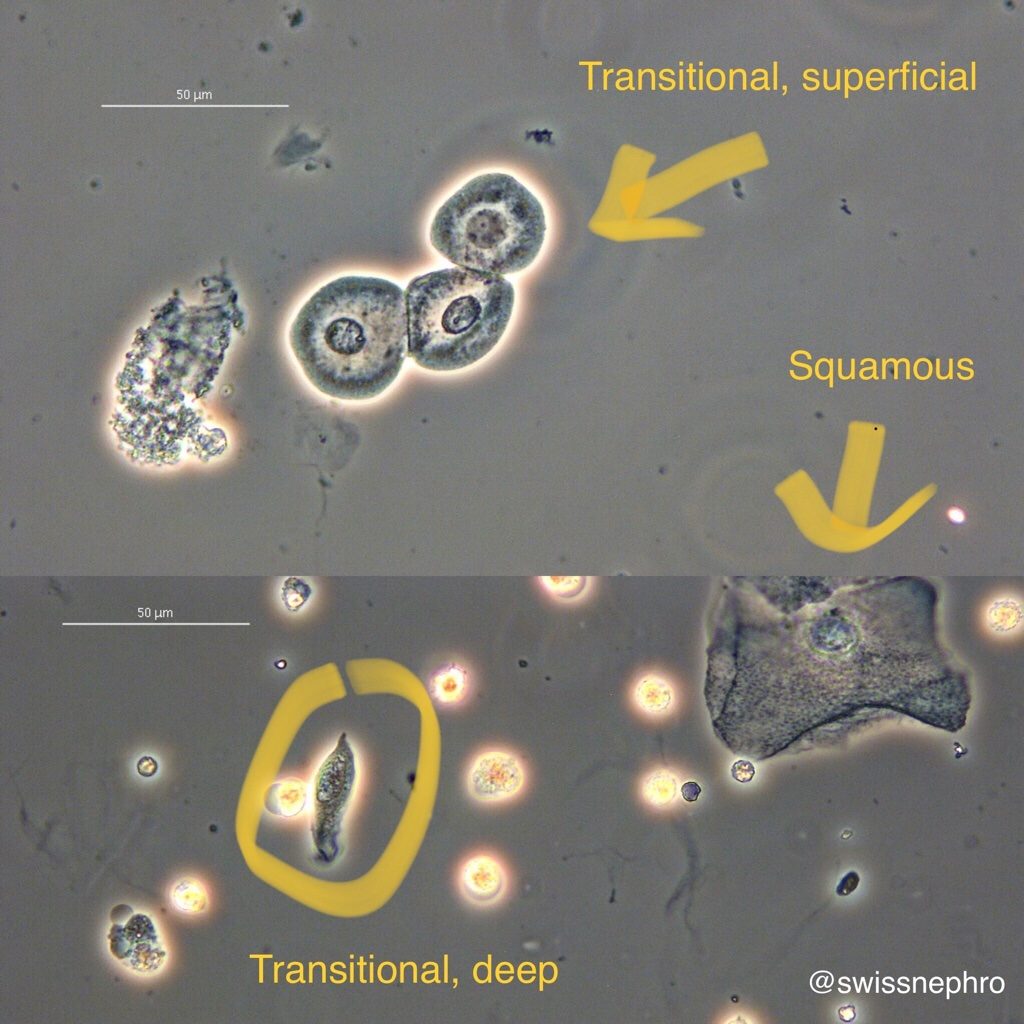

Transitional epithelial (or urothelial) cells come in various shapes. Superficial cells resemble fried eggs with large, round nuclei and relevant amounts of cytoplasm (Fig. 5). Cells from the deeper layers have much less cytoplasm and often tails or pointed cellular extensions (Fig. 6).

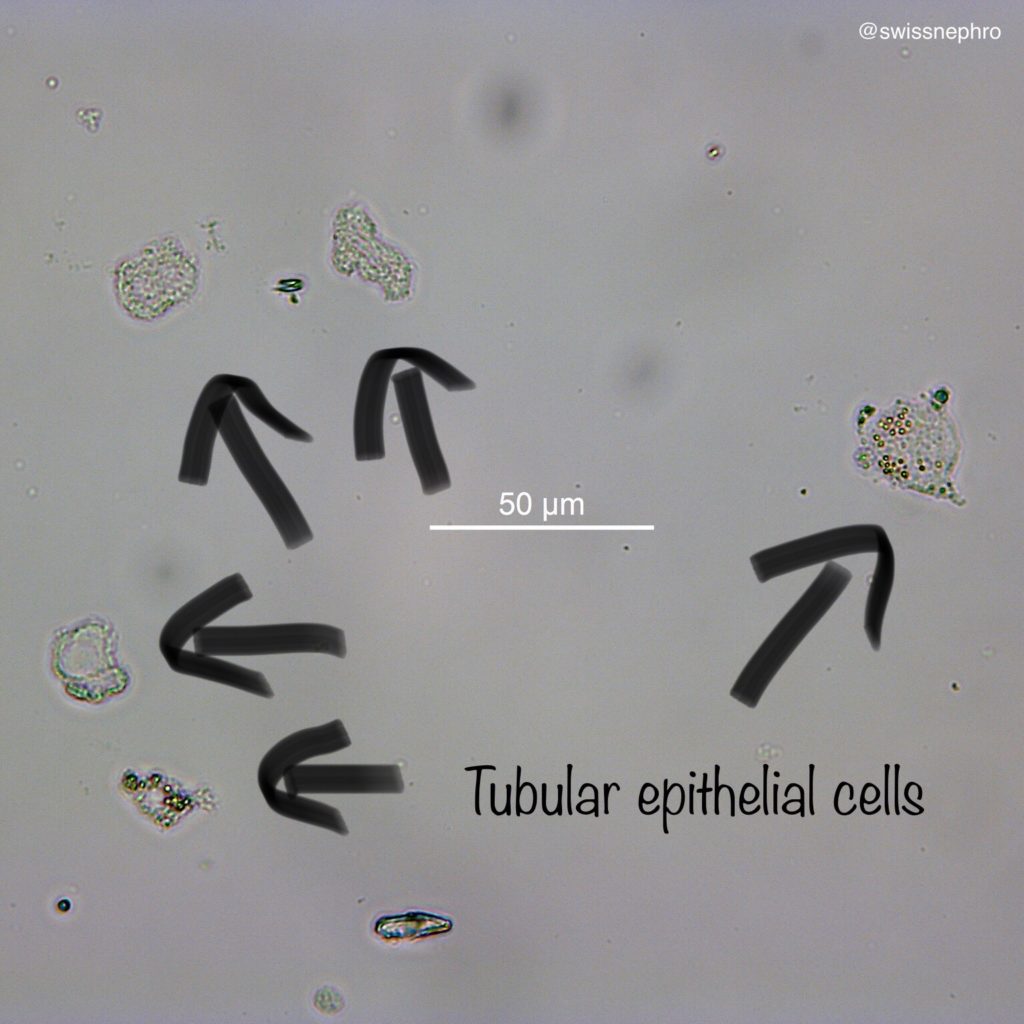

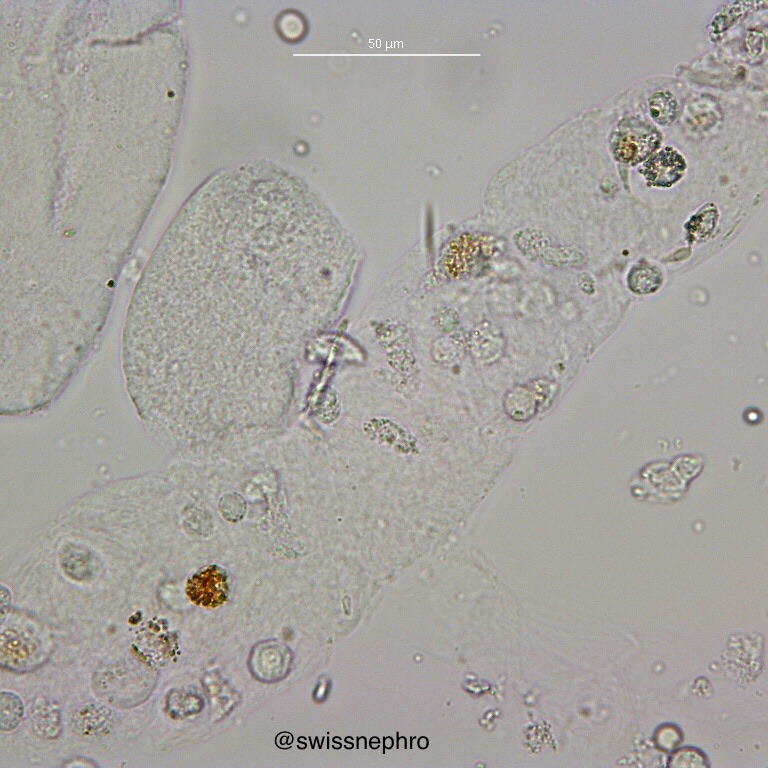

Tubular epithelial cells are an important sign of tubular damage (for oval fat bodies see here). They also have round nuclei and sparse amounts of cytoplasm (Fig. 7 and 8).

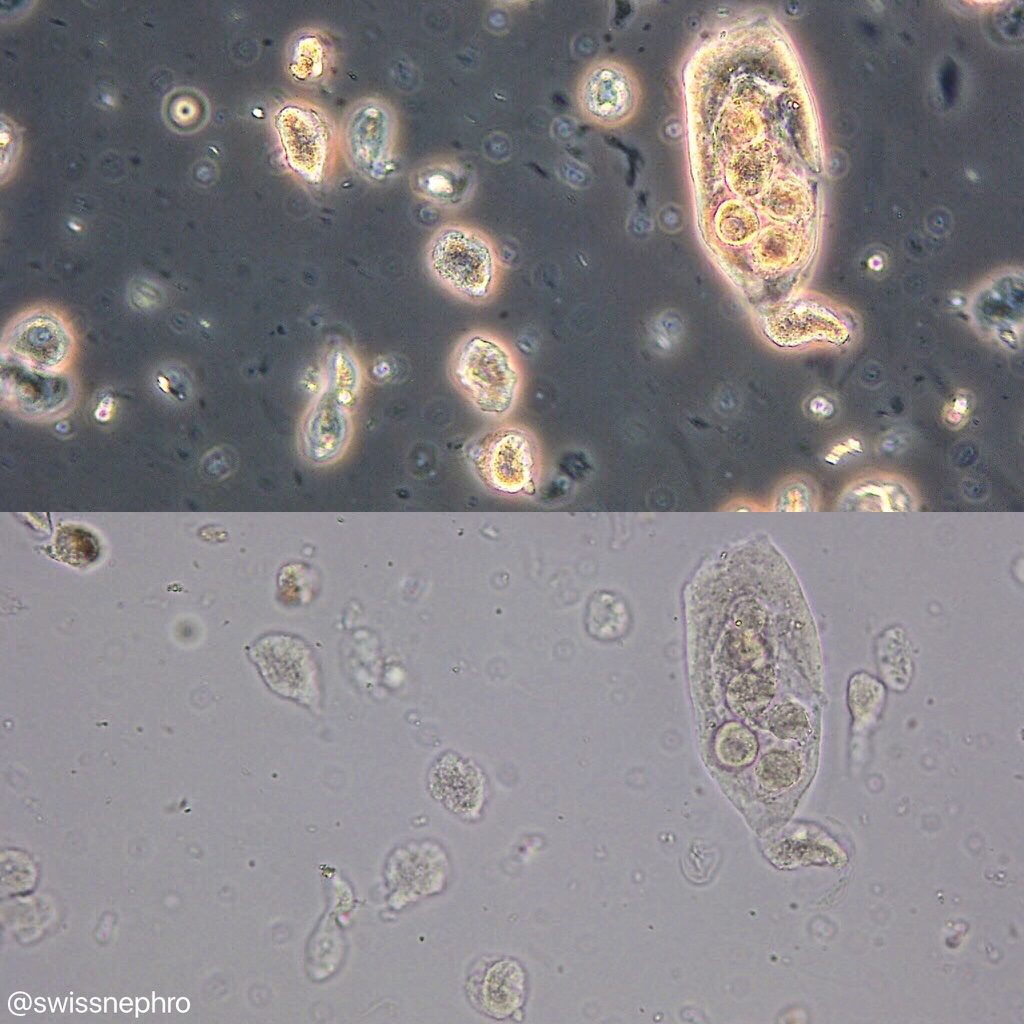

There are two ways to ensure the tubular origin of these cells:

1. Find morphologically identical cells within casts (Fig. 9).

2. Find pigmented inclusions within the cells (Fig. 10 & 11).

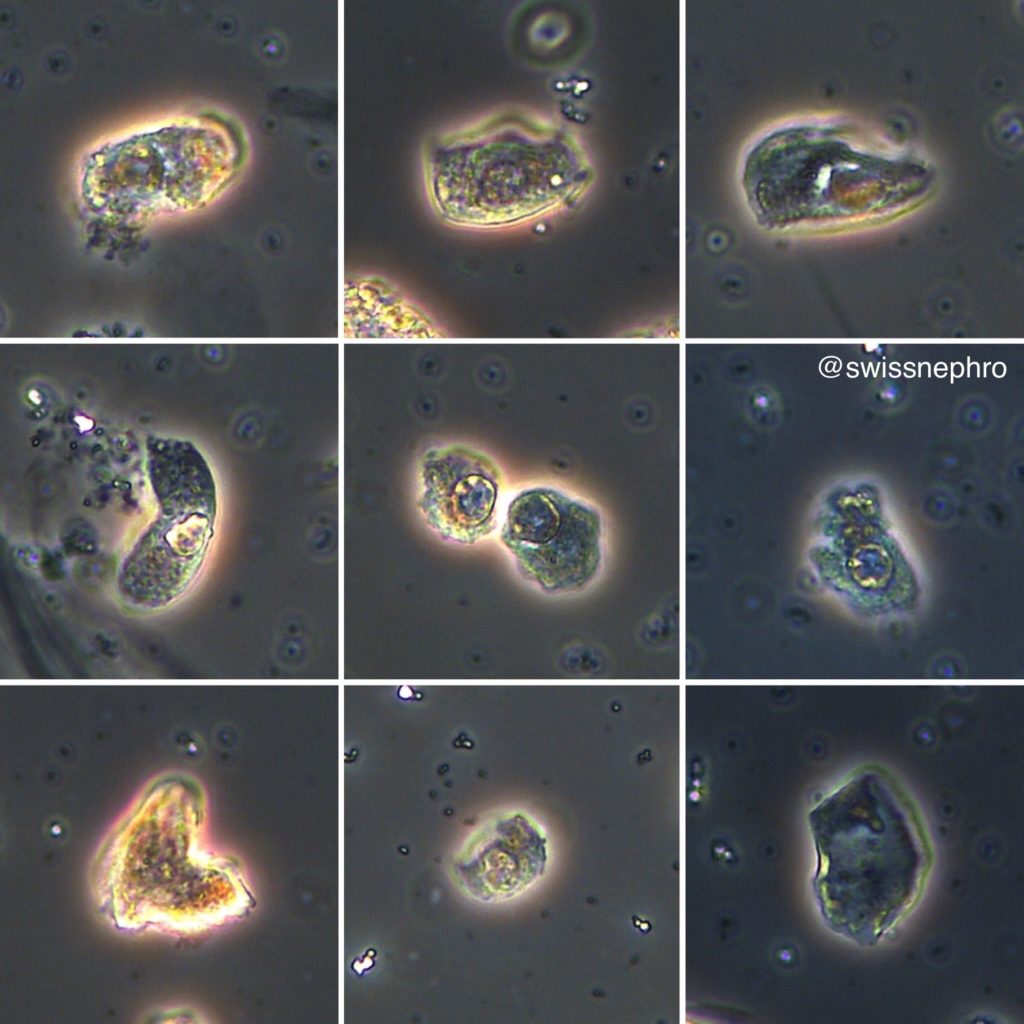

Without these findings, it is often times impossible to reliably distinguish tubular epithelial cells from deep-layer transitional cells by morphology alone. Considering the sediment background can help: In a sediment with extensive muddy brown casts for example, small epithelial cells with round nuclei are usually of tubular origin. In a case with heavy leukocyturia and detectable superficial urothelial cells, they probably represent transitional cells.

All cellular elements in the urinary sediment are prone to degenerative changes caused by osmotic stresses and/or cellular death or dying. You should resist trying to force identification, not every cell can be reliably classified!

Post by: Florian Buchkremer

In your experience, do you tend to see more granulated RTEs in urine sediment vs ungranulated? Is phase contrast a better option vs brightfield light microscopy in identifying or confirming RTEs?