Jade M. Teakell, MD, PhD, FASN

Assistant Professor of Medicine and Associate Program Director of Nephrology Fellowship

McGovern Medical School, Houston TX

@jmteakell

A 62-year-old man with a history of diabetes, hypertension, and kidney failure on peritoneal dialysis (PD) presents with sepsis. A family member found him unconscious and minimally responsive at home. He was brought to the emergency center and found to be confused, febrile, hypotensive, and hypoxic. Temperature 38.5 °C, blood pressure 87/55 mm Hg, pulse 110 bpm, respiratory rate 25 bpm, oxygen saturation 80%, weight 88 kg. He was subsequently intubated for acute hypoxic respiratory failure. Blood, PD effluent, sputum, and urine specimens were sent to the laboratory for culture, and he was started on broad spectrum antibiotics for management of sepsis. Despite fluid resuscitation, he required low dose norepinephrine to maintain adequate blood pressure. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and the nephrology service is consulted for management of kidney failure.

PD prescription at home: 4 nighttime exchanges of 2.5 L over 9 hours followed by a 2 L day dwell all with 2.5% dextrose-containing dialysate. Weekly Kt/V is 1.9 and his estimated dry weight is 85 kilograms (height 180 cm). Has been on this modality for 5 years.

Initial laboratory values reveal sodium 139 mmol/L, potassium 5.7 mmol/L, chloride 100 mmol/L, CO2 23 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 63 mg/dL, creatinine 10.1 mg/dL, glucose 115 mg/dL, calcium 9.0 mg/dL, hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) count 15000 cells/uL, and platelet count 200K/uL. Arterial blood gas (2 hours post-intubation) – pH 7.45, pCO2 30 mm Hg, paO2 90 mm Hg. The PD effluent cell count demonstrated scant WBC insufficient for differential and gram stain was negative. Chest radiograph showed a consolidation in the right middle lobe concerning for pneumonia.

How would you manage this patient’s kidney replacement therapy?

- Resume home peritoneal dialysis prescription

- Resume peritoneal dialysis, but increase the number of exchanges per 24 hours

- Place temporary central venous catheter and initiate standard hemodialysis

- Place temporary central venous catheter and initiate continuous venovenous hemodialysis

I think many would select Choice D for this critically ill patient and move on. Continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT) is an appropriate choice, right? Let me convince you that peritoneal dialysis is also a form of CKRT and appropriate to use in this scenario.

Initially explored in the 1920s, peritoneal dialysis was actually the first kidney replacement therapy (KRT) modality used for management of acute kidney injury (AKI). There are more and more emerging studies examining the use of PD in patients with AKI and specifically in those with critical illness (Al-Hwiesh, Ther Apher Dial 2018). Furthermore, the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) recommends that PD be considered a suitable modality for treatment of AKI in all settings (1B, ISPD Guidelines 2020). This applies to continuing PD in patients with established kidney failure who have already been on maintenance PD.

There are limited studies available that solely examine the rates of continued use of peritoneal dialysis use in patients with kidney failure and critical illness (Sirota, 2016), and practices vary regionally/internationally (Szamosfalvi, AJKD 2013; Akbaş, Clin Exp Nephrol 2015). In Canadian studies, the rate of ICU admission among patients on PD is low at 13.3 admissions per 100 patient–years (Khan, Perit Dial Int 2012) compared to rates of ICU admission in the overall ESKD cohort was greater at 19.5 per 100 patient–years (Strijack, JASN 2009). Khan et al. conducted a retrospective cohort analysis, by cross-referencing a PD database with an ICU admission database (Manitoba, Canada, years 1997-2009). They identified the most common reasons for ICU admission in patients on PD (Figure 2), and observed high treatment failure (TF, permanent transition from PD to HD) and mortality rates.

In the cohort, nearly one-fifth (18.9%) of patients on PD admitted to the ICU were converted to HD during that hospitalization, and at the end of 12-months 12% were alive on HD versus 33% alive on PD (Figure 3). As such, TF appears to be a poor prognostic sign. The reasons for TF were not captured, and the HD modality data (intermittent or continuous) was not available. As stated, “The decision to convert a patient to HD is often clinical and prone to subjectivity.” Furthermore, the authors did point out some unique characteristics of the Manitoba dialysis patient population and acknowledge limited generalizability of the results (Khan, Perit Dial Int 2012). Treatment failure may be a reflection of the cause of critical illness (severe peritonitis, gastrointestinal pathology, see below), a change in patients’ functional status after critical illness impairing the ability to perform PD, or the transfer to a facility that cannot accommodate the modality. In the US, for example, patients requiring post-hospitalization care in skilled nursing facilities will often require “temporary” transition to HD.

Clark et al., retrospectively evaluated the in-hospital mortality of patients with septic shock (years 1998-2012), comparing chronic dialysis-dependent patients with ESKD to patients not receiving chronic dialysis. The numbers of patients on HD versus PD at time of admission were not specified, nor was there any information about whether PD was continued during ICU care. They found no difference in overall survival between chronic dialysis and non-dialysis patients in the study groups (Clark, Intensive Care Med 2016). This is similar to other studies that have found that although ESKD is associated with increased mortality in the ICU, this effect is mostly a result of comorbidities than ESKD itself (Strijack, JASN 2009).

Why the hesitation to use PD in patients with critical illness? First, there is concern that peritoneal dialysis does not provide adequate clearance nor effective volume removal. Second, increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) could hinder diaphragmatic movement and decrease pulmonary compliance, thus complicating management of mechanical ventilation and/or worsening respiratory failure. Infection is a leading cause of hospitalization in patients with kidney failure on dialysis, with pneumonia, catheter-related bacteremia, and peritonitis being common diagnoses.

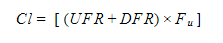

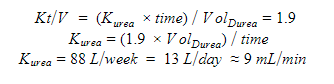

- Can we approximate the clearance of CVVHD with PD? In short, yes. Increased clearance achieved with intermittent hemodialysis requires less time, and increased time on continuous therapy (PD or CVVHD) requires less clearance. Recall that clearance (Kurea) and time (t) are both in the numerator of the adequacy equation Kt/V urea. To estimate the clearance of any solute via CVVHD we can use the following equation (VanLoo, 2017).

Where UFR = ultrafiltration rate, DFR = dialysate flow rate, and Fu = fraction unbound. For example, the estimated urea clearance (KUrea) for standard prescription CVVHD (blood flow 250 mL/min, dialysate flow 2 L/hr, ultrafiltration rate 50 mL/hr ) is approximately 34 mL/min.

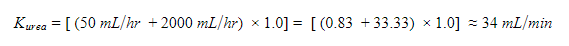

We typically think of peritoneal dialysis clearance in weekly Kt/V, but we can make this information useful in comparing clearances of PD and CVVHD. Knowing the patient’s recent weekly Kt/V urea and his volume of distribution of urea, a simple back-calculation can give an estimate of the urea clearance Kurea in mL/min. The volume of distribution of urea VDurea (total body water) for this patient is 46.3L (Hume-Weyers). For simplification, you could also use 0.6 x patient’s weight (RFN Calculating TBW).

While this calculation is not necessary for each individual patient, this exercise demonstrates the estimated clearance from a standard maintenance PD prescription in values we can relate to CVVHD. In CVVHD, the clearance is directly related to the dialysate flow rate; a change in the blood flow does not have a meaningful effect on clearance. As such, increasing the clearance with PD is directly related to increasing the total dialysate volume . We can think of the PD dialysate flow rate as liters instilled per 24 hours. By utilizing continuous exchanges over a 24-hour period, rather than limiting to nighttime cycles and long day dwell (Choice A), we can in effect double or even triple the daily clearance (Choice B). The ISPD recommends a target of 0.5 daily Kt/V (or 3.5 weekly Kt/V) in critically ill patients with AKI which provides outcomes comparable to that of daily HD (1B, ISPD Guidelines 2020). A few extra exchanges in a 24 hour period (added to patient’s home prescription) can easily increase daily Kt/V to provide additional clearance that might be needed during critical illness.

2. Does intra-abdominal pressure from peritoneal dialysis affect ventilator management? Increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP > 12 mm Hg or 16 cm H2O) and especially abdominal compartment syndrome (sustained IAP > 20 mm Hg or 27 cm H2O) can attenuate diaphragmatic movement, decrease pulmonary compliance, and decrease total pulmonary capacity (Toens, Shock 2002; Pelosi, Acta Clin Belg 2007). However, peritoneal dialysis at typical fill volumes does not increase IAP to this degree. Normal IAP of an empty abdomen is low at 0.5 to 2 cm H2O, but in the setting of critical illness IAPs of 6 to 9 cm H2O can be considered normal. The IAP increases to 10-15 cm H2O with the infusion of 2 to 3 L of dialysate fluid (Gotloib, Peritoneal Dial Bull 1981). A recent prospective cohort study (Almeida, Clin Exp Nephrol 2018) evaluated 154 patients with AKI (37 on continuous high-volume PD and 94 on 6x/week HD) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation to determine effects of dialysis modality on respiratory mechanics. Both groups had improvement in volume status and oxygenation, with no significant difference in pulmonary compliance or respiratory system resistance between the two groups. The IAP measured pre- and post-PD during the study showed only a temporary increase, maximum was 10.2 ± 5.9 mm Hg. The IAP returned to values very close to basal levels (8 to 9 mm Hg) by the third day, and overall PD caused no impairment in respiratory mechanics. If there is still concern from the intensivist, we can lower initial fill volumes and gradually titrate up as tolerated. Furthermore, the IAP can be monitored with a goal of less than 13 mm Hg (or 18 cm H2O), and patients can be readily drained to assess if there are any real-time effects on ventilation mechanics (Shimonov, CJASN 2020).

When is PD contraindicated in critical illness?

If the patient was otherwise doing well with maintenance PD, and there is reasonable expectation for recovery (e.g. weaning pressors, few ventilator days), then continuation of PD may be in the patient’s best interest. However, a few scenarios do necessitate transition from PD to HD. Severe polymicrobial or fungal peritonitis warrants timely removal of the PD catheter. Patients presenting with bowel ischemia or infarction, bowel perforation, or those requiring an open abdominal surgery may not be suitable for PD.

If we DO need to transition patients to temporary hemodialysis, DON’T forget about the PD catheter. If the PD catheter is to remain in place, it should be meticulously cared for. There are things that can be done during the ICU course that can prevent infectious, mechanical, and/or adequacy complications down the road.

- Timely exit site care with dressing changes

- Education/awareness (it is NOT a feeding tube!)

- Strategize to preserve residual renal function, if present

- Intermittent small volume flush to maintain catheter patency (every 2-4 weeks)

Reviewed by Nayan Arora, S. Sudha Mannemuddhu, Matthew A. Sparks, Amy Yau

Have you found that continued PD significantly impacts tachycardia/hypotension in a patient who is on and off low dose vasopressors over several days?

Figure 1 is adapted from Blood Purif 2016 42(3): 224-237.

-jmt