Welcome to the 15th case of the Skeleton Key Group, a team of 40 – odd nephrology fellows who work together to build a monthly education package for the Renal Fellow Network. The cases are actual cases (without patient identifying information) that intrigued the treating fellow.

Written by: Sarah Mirembe

Visual Abstract: Bilal Khalid

A. The Stem

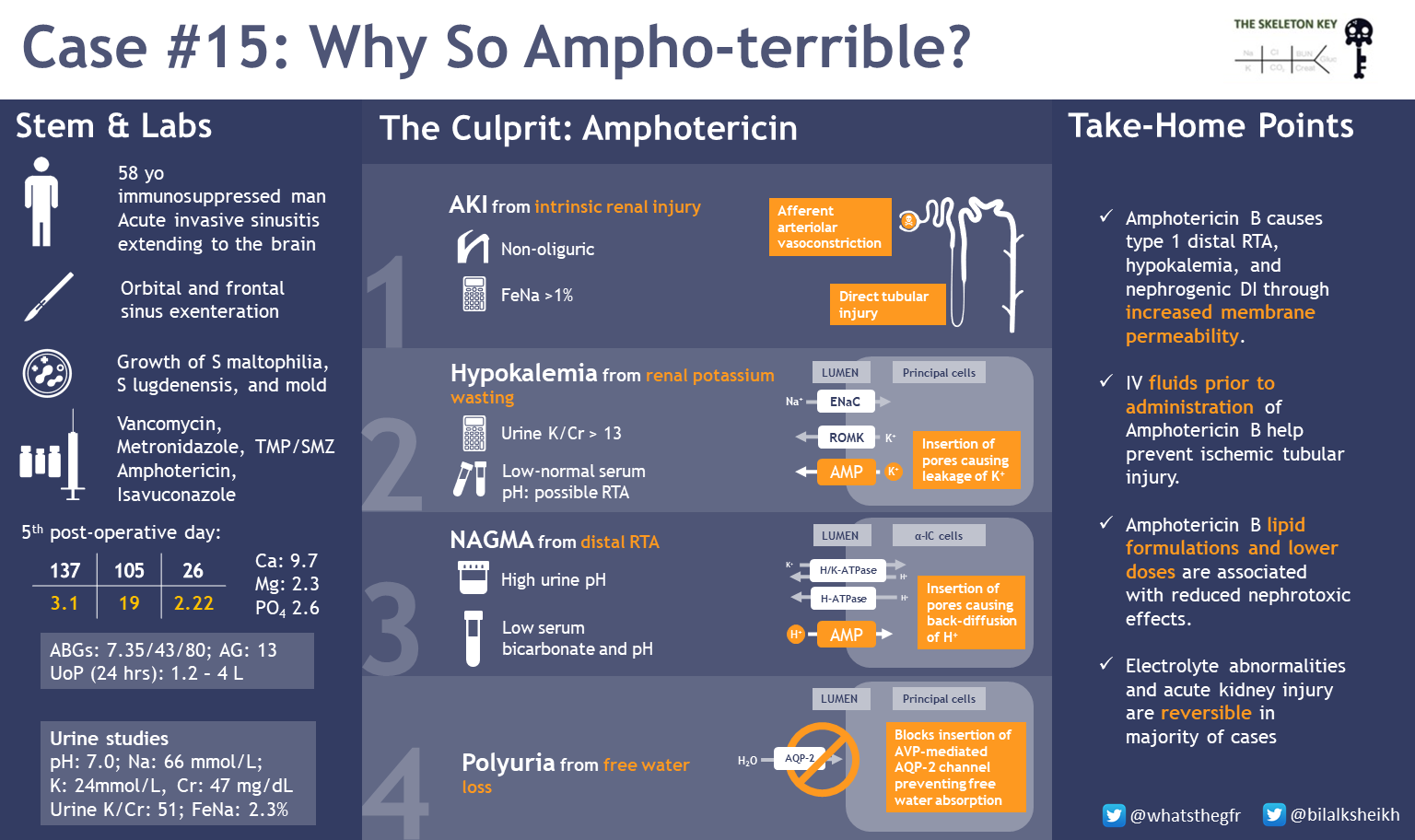

A 58-year-old man presents with a 7-day history of right eye swelling and pain with eye movements with no accompanying vision changes.

He has a history of atrial fibrillation, ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm, and mixed T cell myeloid leukemia, last treated 5 months ago with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone. He has developed pancytopenia secondary to chemotherapy over the last 3 months.

He was admitted with intracranial and orbital infection. Imaging showed preseptal/periorbital cellulitis, acute invasive sinusitis with necrotic tissue extending to the right frontal lobe with abscess formation and vasogenic edema. Ophthalmology performed orbital decompression and right orbital exenteration. Neurosurgery performed right frontal craniotomy and frontal sinus exenteration. Microbiologic studies showed fungal elements resembling mold, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Patient was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics and antifungals throughout his hospital course with vancomycin, metronidazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, amphotericin (medication was given with 1L normal saline pre-infusion and 250 ml normal saline IV piggyback daily), and isavuconazole.

On day 6 of his hospital admission, you are consulted for electrolyte abnormalities and acute kidney injury (AKI). He denies vomiting or diarrhea, and is tolerating oral feeding well. Patient is non-oliguric; urine output has been around 2-3 L per day.

Vital Signs:

BP: 123/90 mm Hg HR: 79 bpm RR: 10 min SpO2: 91% on 3 L/min Oxygen via facemask Temperature: 97.5°F (36.4° C)

Physical Exam

General: Awake, alert, follows commands, no acute distress

HEENT: Right eye s/p exenteration, scalp surgical incision clean and dry

CV/Heart: Unremarkable

Chest/Pulmonary: Unremarkable

Abdomen: Unremarkable

Extremities: No pitting edema, 5/5 strength in all extremities with full ROM.

Nervous System: CN’s 2-12 intact, Deep Tendon Reflexes 2+ throughout, sensation intact.

The rest of the physical exam is otherwise unremarkable.

B. The Labs

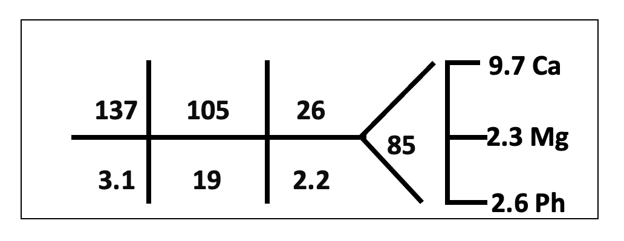

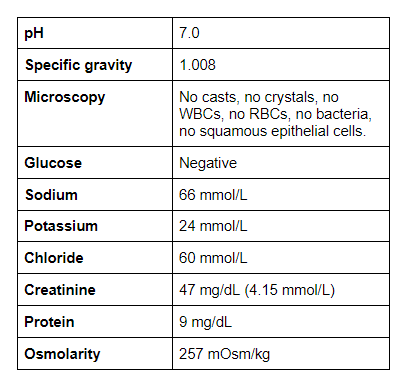

Blood Chemistries

The patient’s baseline Cr was 1.4 but had increased to 2.2 at the time of consultation.

Potassium and bicarbonate were normal previously. Albumin 3.9.

Anion gap: 13 Corrected anion gap: 13.3

Urinalysis and Urine Chemistries

As nephrologists, we love to calculate. Let’s go through a few important ones below:

Urine protein/Cr ratio: 191 mg/g creatinine. reference range (<170)

Urine K/Cr ratio = 51 mmol/g (5.7 mmol/mmol).

Fractional Excretion of Sodium (FeNa) = 2.3%

C. Differential Diagnosis

To summarize, we have a patient with an invasive fungal sinusitis extending to his brain, with associated AKI, hypokalemia, and a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis after being treated with multiple antifungals and antibiotics.

- In regard to the AKI, the FeNa > 1% suggests an intrinsic renal disorder as there was no evidence of hydronephrosis or bladder outlet obstruction.

- The hypokalemia with elevated K/Cr ratio (51 mmol/g) is consistent with renal potassium losses. Review how to assess for renal potassium wasting in our previous post! A K/Cr ratio of < 13 mEq/g or <1.5 mEq/mmol suggests appropriate kidney response to hypokalemia. Ratio of higher than that could be from kidney wasting.

- Tubular dysfunction seems likely given the impaired kidney handling of potassium, although one cannot rule out increased aldosterone or aldosterone-like effect contributing.

Using Occam’s razor, can we deduce an etiology for our patient’s AKI and hypokalemia?

| Differentials for hypokalemia due to renal potassium wasting include: |

| Direct Tubular Injury from amphotericin B, vancomycin, chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide. |

| Hypomagnesemia, hypercalcemia, and diuretic use can also lead to renal K wasting but are not present in this case. |

| Medications such as lithium can cause tubulopathies and diabetes insipidus which may lead to renal potassium wasting through the collecting ducts BK or ROMK channels (not present in this case). |

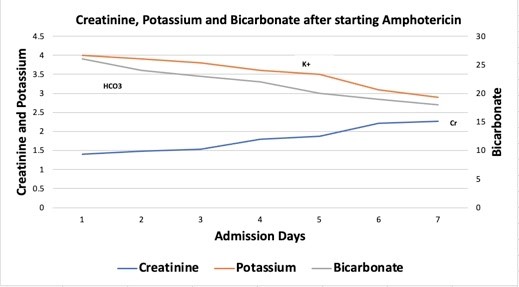

The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin 800 mg IV every 24 hours (5 mg/kg/day) 4 days prior to AKI. Below are the creatinine and electrolyte trends after starting amphotericin on day 1.

D. The Diagnosis

We diagnosed our patient with Amphotericin B Nephrotoxicity.

E. More Data

How does amphotericin cause nephrotoxicity?

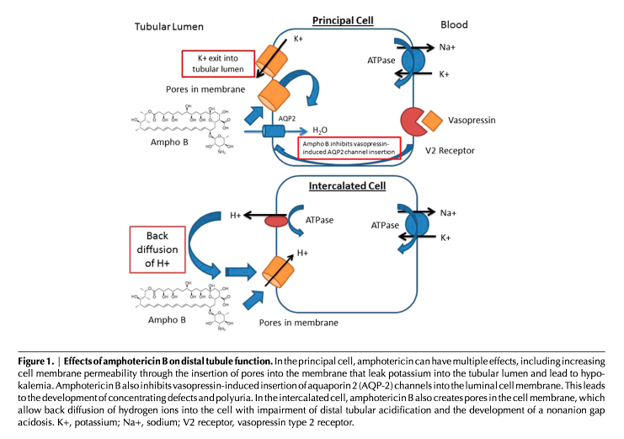

- Elevated creatinine is partially a result of direct tubular toxicity: amphotericin B binds to sterols in cell membranes, resulting in pores. This ionic permeability can lead to tubular injury with consequent electrolyte abnormalities and programmed cell death.

- Amphotericin also leads to a pre-renal AKI by direct vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. The mechanism of vasoconstriction is unclear but it is thought to be due to opening calcium channels, impaired nitric oxide release from endothelial damage, and action on vascular smooth muscle cells.

How does amphotericin lead to electrolyte abnormalities and acidosis?

Amphotericin can affect alpha intercalated cells of the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and the collecting duct (CD), leading to Type 1 renal tubular acidosis (RTA) and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (DI).

Amphotericin B creates pores that allow secreted H+ to backleak through the cell membrane down its concentration gradient. In addition to metabolic acidosis, this leads to hypokalemia through (a) renal K+ wasting through decreased reabsorption and (b) leaking of intracellular potassium down its concentration gradient into the urinary luminal space.

Nephrogenic DI can also occur independent of amphotericin. Hypokalemia (often seen in patients with amphotericin) can inhibit AQP2 channel insertion, leading to enhanced aquaresis.

F. Management

Our patient was treated with normal saline, potassium, and bicarbonate repletion. His kidney function and electrolyte abnormalities subsequently improved after he completed the amphotericin course. The decision to discontinue is a discussion with infectious disease and weighing the risk and benefits of continuing.

Why does treatment with intravenous fluids help?

Volume expansion with isotonic intravenous fluids help increase renal blood flow, thereby mitigating the decline in GFR and subsequent amphotericin nephrotoxicity. Additionally, balanced fluids such as lactated ringers can help correct the acidosis and hypokalemia.

What is the risk of nephrotoxicity with amphotericin?

Risk factors for nephrotoxicity include use of higher doses, concurrent use of other nephrotoxic medications including antibiotics, nephrotoxic agents including contrast, and a history of chronic kidney disease.

The formulation of amphotericin B also affects risk of nephrotoxicity. Conventional amphotericin contains deoxycholate, which is directly toxic to tubules. The meta-analysis by Aguirre et al reported liposomal formulations are less nephrotoxic (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.40-0.59) because of preferable distribution through the reticuloendothelial system and macrophages and increased delivery to organisms rather than host tissue.

Tubular defects appear to be dose related and precede the decline in GFR. Thankfully, it appears the electrolyte abnormalities and AKI are reversible in the majority of cases, although 15% of patients progress to renal failure and require dialysis.

G. Take-Home Points

- Amphotericin B causes type 1 distal RTA, hypokalemia, and nephrogenic DI through backleak of H+ and increased membrane permeability.

- Giving isotonic IV fluids prior to the administration of amphotericin B may help prevent AKI.

- Amphotericin B lipid formulations and lower doses are associated with reduced nephrotoxic effects.

Sadly you were not discussing the nephrotoxic effect of vancomycine and the drug-drug-interaction of vanco and AmB.

Nice discussion